Lexicography in the French Caribbean: An assessment of future opportunities

Jason F. Siegel

The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus

E-mail: jason.siegel@cavehill.uwi.edu

1 Introduction

Overseas French (le français d’outre-mer) is a fairly important topic in French linguistics. But so far, the French varieties of the Antilles and French Guiana receive less attention than French-based Creoles spoken in the same region. However, it is important, especially during this UN Decade for People of African Descent, to report not only on varieties of French spoken in Haiti, Guadeloupe, Martinique, St Barthelemy, St Martin and French Guiana, but to give a full account of the lexicographic work that remains to be done in these territories called the “French-official Caribbean” (Alleyne 1985). [1] Indeed, given a certain quantitative decreolization (Rickford 1987), a loss of creolophones (i.e. Creole-speakers) in the face of French glottophagy, it is important to know these varieties. In particular, there is much that remains to be done in the lexicographic field. While the Spanish-speaking Caribbean has bureaus of the Royal Spanish Academy dedicated in part to documenting the lexical particularities of each country or territory, the French-official Caribbean has no such body that operates over its whole territory. There are very few dictionaries of the French spoken in this region, despite the fact that there are hundreds of thousands of Francophones in the area. Here, I will review the lexicographic work, whether in the form of dictionaries or large glossaries, that has already been done in the Caribbean. I will also discuss the various territories and the kinds of dictionaries that would be useful there. I will conclude with an evaluation of the role that can be played by the Richard & Jeannette Allsopp Centre for Caribbean Lexicography at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus in Barbados.

2 Lexicography in the French-official Caribbean Through Today

Lexicography in the Caribbean dates from the seventeenth century, with the publication of Breton (1665). A missionary in Dominica, Father Breton knew the Amerindians who lived there very well. He therefore learned their language during his long evangelization of the people, which did not have much success except the relative goodness between the missionaries and the Caribbean people. He was able to learn the Caribbean language with the help of an indigenous interpreter (Pury 1999: XXVIII), thus he started writing a dictionary of the language, hoping that the missionaries who arrived after him could continue to evangelize in the language of the people. It is clear, therefore, that the first dictionary in the Caribbean is a bilingual dictionary. From then on, this is the norm for lexicography in the French West Indies. Only bilingual dictionaries appear until 1997 (Telchid 1997).

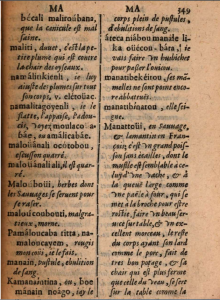

The dictionary does not have the form that we know today. It is an alphabetical list of words and sentences, but it is not clear that the sentences described are lexemes. Lemmas are often two or three words, and Breton often provides translations in the form of a complete sentence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Extract from Breton (1665)

After France ceded control to the British of the islands where the Amerindians lived (and later died out), there was no great tradition of bilingual lexicography of Amerindian languages in the French-speaking Caribbean, because the purpose of such dictionaries or glossaries was to help missionaries evangelize those who did not know Christianity. Without access to this population thanks to British conquests and genocide, the motivation to compile a dictionary disappeared.

There appears almost a century later a dictionary of the Galibis of French Guiana by La Salle de l’Étang (1763). Unlike Breton (1665), this bilingual dictionary is bidirectional, so readers could search for the French word to express themselves in Galibi or the word in Galibi to understand what the Native Americans said. There are also critiques of the language which indicate where the syntax of Galibi is different from that of French, in addition to interlinear glosses for the examples. Another edition a century later adds Latin glosses for each French lemma.

We must wait until the twentieth century for other French dictionaries in this region. Élodie Jourdain (1956) produced a vocabulary, organized by themes, of Martinican Creole. Pradel Pompilus (1958) made a lexicon of Haitian Creole. These two creoles, like the other creole languages, were long regarded as languages inferior to European languages. It is not surprising that French lexicographers have therefore ignored them. But the contrast between these two linguists is very important: Jourdain was a béké, that is to say a white Martinican, and wanted to show the deformation of French by the blacks (Aub-Buscher 2003: 2). On the other hand, Pompilus was a black Haitian who was proud of his language, wanting to promote the knowledge of Haitian letters. This pride in the language of all Haitians plays an important role in the proliferation of Haitian Creole dictionaries. Today, it is the Caribbean Creole language that has by far the largest number of dictionaries (Skybina & Bitko 2014).

Today, there is at least one dictionary for every French Creole spoken in the French-speaking Caribbean (see Table 1), in addition to several dictionaries of the French Creoles spoken in Saint Lucia, Dominica, Louisiana and Amapá (Brazil). The French Creoles of Trinidad, Venezuela, Grenada and San Miguel (Panama) still do not have a dictionary. In addition, there are dictionaries in the French-official Caribbean of proverbs (Confiant 2004, Pinalie & Confiant 1994), a dictionary of Creole neologisms (Confiant 2003), and a two-volume etymological dictionary (Bollée 2017). However, the Atlantic zone is not monolingual in Creole. There are also varieties of French, many of which are strongly influenced by Creole, including Haitian French, Antillean French and Saint Barthelemy “Patois”. Yet, there is only one dictionary, of Antillean French, which is described by Aub-Buscher (2003: 4) as “not altogether satisfactory”. Haitian French, used by more speakers than several French Creoles, has no dictionary. In addition, there are dictionaries of Amerindian languages: Wayampi (Grenand 1989), Arawak/Lokono (Patte 2012) and Wayana (Camargo & Tom 2010) and of English creoles spoken in French Guiana such as the dictionary of Aluku (Maïs n.d.).

| Region | Dictionaries |

| Guadeloupe | Bazerque (1969), Ludwig et al. (1990) |

| Martinique | Pinalie (1992), Confiant (2007) |

| Haiti | Valdman & Iskrova (2007), Valdman et. al (2017) |

| French Guiana | Contout (1992), Barthélemi (2007) |

| Dominica | Fontaine (1991) |

| St Lucia | Jones & Carrington (1992), Crosbie et al. (2001) |

| Louisiana | Valdman et al. (1998) |

| Amapá | Tobler (1987) |

Table 1: (Some) Dictionaries of Atlantic French Creoles.

The dictionaries that exist are sometimes of excellent quality, sometimes of mediocre quality. For example, there is the huge Haitian-English Creole Bilingual Dictionary of Valdman & Iskrova (2007), which has been lauded by many Creole-speaking readers and has a much wider nomenclature than most Creole dictionaries, and its new complement English-Haitian Creole, reverse engineered from the former (Valdman et al. 2017). The difference between homonymy and polysemy, criticized in the dictionaries of the Lesser Antilles by Hazaël-Massieux (2002), is given sufficient attention here. On the other hand, in French Guiana, Barthelemi (2007) is a totally inadequate dictionary for this Creole. It does not distinguish between homonymy and polysemy, and there are many essential omissions of vocabulary, including ‘uncle’ and ‘sister’ and many errors of meaning and nomenclature.

3 The Lexicographic Needs of the French-official Caribbean

There is obviously quite a bit of work to be done in the lexicographic field in the Caribbean. Here, I present six paths to pursue:

1) the documentation of Saint-Barthélemy French

2) multilingual lexicography between the languages of the French-official Caribbean and the languages of the rest of the region

3) lexicography of the languages of Guyana

4) English dialects, including Gustavia English and St. Martin English

5) the dialects of regional standard French

6) signed language

3.1 St Barthélemy French

The local variety of French spoken in St Barth is in urgent need of documentation, as it is probably moribund. The acculturation of the metropolis is replacing the ‘patois’ of the island with standard French (Maher 2013). The dialect stands out because it is the only one in the region that is not strongly influenced by the omnipresence of a Creole. Indeed, Maher indicates that those who speak what they themselves call Patois on the island do not belong to the same community as those who speak Creole, which came to the island from Guadeloupe with slaves in the eighteenth century. The patois will most closely resemble colonial French, spoken by white settlers when French Creoles developed in the region (Valdman 1969-70: 78, cited in Maher 2013: 123). It is therefore of extreme importance from the point of view of Creolists to document as much as possible the ‘patois’ of this island, which may well evince some of the conservative traits of French-based Creole’s lexicons, such as Haitian Creole’s continued use of pistach to mean ‘peanut’, while French now uses that same form to mean ‘pistachio’ (employing cacahuète or arachide to denote ‘peanut’).

Until now, there is no lexicographic document freely available on this variety. There is a glossary by Gilles Lefebre of the University of Montreal dating from the 1970s, but it is to be consulted only in situ at the Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence. See Figure 2 for an example. Thus the community does not even have access to the only lexicographic document of their own variety of French. The same goes for linguists, both Creole and dialectologists. Research on this variety comes up against further pitfalls: the physical destruction of the island after the hurricanes of 2017 and the lack of trust from the St Barths to linguists. The hurricane displaced many of the island’s residents, and consequently their knowledge of the dialect. The lack of confidence is due to the arrival of a journalist who visited the island in the 1950s and who stunned the friends he had made by denigrating the people as backward (Maher 2013). So it is quite difficult to do the necessary work before the disappearance of the dialect. If we successfully manage to convince the St Barths who still remain to participate in these researches, it will take a differential lexicon, a lexicon that shows the lemmas that are absent from the standard or are different there. It will also require a multilingual glossary, given the presence of a French-based Creole, a local variety of English and Standard French on the island.

Figure 2: Extract from Lefebre (n.d.)

3.2 Transregional Multilingual Lexicography

The next task for the lexicographers of the French-speaking Caribbean is the multilingual lexicography of the region. Admittedly, there have been bilingual dictionaries for the region since the beginning, but there are quite few dictionaries that aim to connect the parts of the Caribbean that do not share the same official language. That is, there are many bilingual dictionaries for the languages of the same community – English-Creole in St. Lucia or Dominica, French-Creole in the French West Indies and French-Wayana in French Guiana. On the other hand, Haiti has the only Caribbean Creole for which there is a lexicographic tradition between Creole and a language that is not official in its territory (English and Spanish), reflecting its status both as the largest Creole language of the region as well as its complex history with the nearby countries of the United States and the Dominican Republic. Recently Cocote (2017) has produced a thesis that translates regional Antillean French to Cuban Spanish. On the other hand, for creoles, there is no dictionary that allows users to compare the meanings in the French Creoles of Dominica and Martinique, for example, since the official language of the former is English and that of the latter is French. Such a pan-Creole dictionary would be very useful for linguists (as the Atlas linguïstique des Petites Antilles (Le Dû & Brun-Trigaud 2013) demonstrates). In addition, the quality of Creole dictionaries varies greatly (Hazaël-Massieux 2002), with excellent dictionaries for Haitian Creole, but poor dictionaries of French Guianese Creole. A methodological rigor and a pan-Creole corpus could only improve the bilingual dictionaries produced in the region.

In addition, there is only one dictionary that attempts to span most of the Caribbean region: the Caribbean Multilingual Dictionary of Flora, Fauna & Foods (J. Allsopp 2003), an expansion of Jeannette Allsopp’s contribution to the Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (R. Allsopp 1996). It is the only dictionary that translates lemmas from Caribbean English into French, French Creole and Spanish. The dictionary is the result of decades of research, and is only the first volume of several regional dictionaries aimed at promoting knowledge of the cultural and linguistic foundation that is shared by the entire region, despite the official languages. There is a second volume in preparation expanding the scope to include religion, music and dance, and more efforts will be needed to keep the lexicography relevant to the entire region. For example, a subsequent edition could be produced that allows easy look-up in any language, not just in Caribbean English as the current dictionary requires.

3.3 Dictionaries of the Regional Languages of French Guiana

Bi- and multilingual lexicography in the French-official Caribbean cannot be limited to traversing the official-language boundaries of the Caribbean, but must also take place within the French Caribbean as well, namely in French Guiana. French Guiana is the department and region of France with the highest number of officially recognized regional and minority languages. Foremost among them is the French-based creole endemic to the territory, which enjoys a privileged position among the regional languages, serving as a lingua franca among the many different ethnic groups of the territory. There are also Amerindian languages such as Wayampi, Emerillon, Lokono, and Wayana, as well as English-based creoles such as Paramaka, Aluku and Ndyuka, shared with Suriname. Finally, the Hmong language of Southeast Asia has a well-established presence, hte Homng people having been resettled there as a form of asylum after fighting alongside the French in their loss of the War in Indochina.

Despite this rich multilingualism and a high value placed on diversity in the region, too few dictionaries of the region have been produced. There has been some recent effort on this front led by Bettina Migge and Isabelle Léglise, linguists at the Center for the Study of Indigenous Languages of the Americas in Paris (CELIA), with dictionaries of the English- and French-based creoles and Amerindian languages under production. These dictionaries will be bilingual, translated into either French or Dutch. Still, only five dictionaries are being produced, leaving half the languages of French Guiana without a dictionary. In light of the acculturation project that France continues to enforce within its territories, the documentation of these varieties is as urgent as ever.

3.4 English dialects of the French-official Caribbean

Fourth, there is a largely pristine area of lexicographic work to be done on the English varieties of the French Caribbean. Because English is spoken by far fewer people in the Caribbean than Spanish, French or French creoles (Allsopp 2003), it may be surprising that it has long-established communities of native speakers in all the official-language regions of the Caribbean, including groups in the Samaná peninsula of the Dominican Republic, the SSS islands (Saba, Saint Eustatius and Sint Maarten) and of course the French-official Caribbean. The English dialects are spoken on two islands of the French Caribbean, Saint Martin and Saint Barth. Saint Martin is mainly an Anglophone island, with people learning as second languages the European standard varieties of French or Dutch, depending on the side of the island on which they grow up. Still, this dialect remains poorly studied from a lexical perspective, and projects like the Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage exclude it from their scope, since it is not found in the English-official Caribbean. The dialect of English found in St Barth is spoken principally in Gustavia, and dates back to the colonial era when St Barth was owned by Sweden (Maher 2013). Sweden never seriously got into the establishment of Caribbean colonies, and used English as its language of trade in the region. The dialect persisted even after St Barth returned to French control. While some preliminary research (Decker 2004) has been conducted on this variety, showing some distinctive lexical elements such as the use of day as a locative copula, Gustavia English remains underdocumented, and like the local French dialect, it remains under threat of extinction by physical displacement and French acculturation.

3.5 Regional Standard French Dialects

While regional languages of the French-official Caribbean are in need of lexical documentation, the regional French dialects mutually intelligible with European Standard French are similarly in need of dictionaries. There is currently a small differential dictionary of Antillean Regional French (Telchid 2007), but no similar dictionary for the standard French of Haiti, which has been shown by Étienne (2005) to be lexically distinctive from the French of Europe with words such as maisonette ‘any small house’, souventes fois ‘oftentimes’, déchoucage ‘uprooting’ and Primature ‘Office of the Prime Minister’. Given the volume of French produced in Haiti on a daily basis in the press and in government communication as well as French-language literary work, there is ample opportunity to quickly assemble a corpus on which to base a dictionary of the French of Haiti as well as a larger dictionary of Antillean French. Similarly, the French of French Guiana is likely in need of documentation: while Authors (YEAR) maintain that the French dialect spoken there is essentially just European Standard French, my own fieldwork in the region of only a few months has demonstrated the presence of some regionalisms such as dégrad ‘jetty’ (Standard French débarcadère), bacove ‘banana’ (Standard French banane), boulin boulino ‘duck duck goose’ (Standard French chandelle, facteur), and maypouri ‘tapir’ (Standard French tapir). There are likely many more regionalisms to be found under the influence of the local languages.

3.6 French-official Caribbean Signed Language Varieties

Lastly, there is exploratory work to be done on the signed language varieties of the French Caribbean. French Sign Language is taught everywhere in the French-official Caribbean except for Haiti, which teaches American Sign Language. However, there is as yet no research into the lexical particularities of French Sign Language in the overseas departments and regions. Just as we saw a number of regionalisms in the overseas departments of French, given the differences between European and Caribbean realities, we must expect that a number of regionalisms would exist in the Caribbean varieties of French Sign Language. Similarly, we would expect that same difference to apply to the variety of American Sign Language taught in Haiti. Fieldwork is therefore needed among experts in these related signed languages.

Beyond regionalisms in the coloniser languages, there is an open question about the lexicons of any community signed languages. Some collaborative research between the deaf university Gallaudet University in the United States, the Organization of American States, and the Office of the Secretary of State for the Integration of Handicapped People in Haiti has already begun, documenting the properties of Haitian Sign Language, an indigenous variety mutually unintelligible with the local American Sign Language variety (Bureau 2014). There is therefore ample opportunity to describe a large lexicon for a highly vulnerable population. Furthermore, because areas with small gene pools tend to develop deafness over time, it is suspected that St Barth, with its small white population, might have a community signed language to explore as well (Benjamin Braithwaite, p.c., August 5, 2016), and in principle the same arguments might apply to small communities in the rainforests of French Guiana.

Advancements in signed language lexicography are coming out of the English-official Caribbean, which will facilitate look-up strategies in signed languages to get the spoken language equivalent. Normally, signed language dictionaries are organised in a way that allows hearing people to find the signed language equivalent. However, at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus in Trinidad, there is research using motion-sensor technology that is being developed that will allow users of a signed language to sign a word in their native language. This technology will allow a much broader range of lexicographic projects to be pursued, including bilingual, transregional lexicography.

4 Conclusion

There is a wide variety of lexicographic projects that have yet to be attempted and completed, which does not even take into account improvements in the quality of projects that have already been carried out. The Richard & Jeannette Allsopp Centre for Caribbean Lexicography, of which I am the director, is prepared to assist with the execution of any of these projects and to lead a number of them. The Allsopp Centre is the only unit dedicated to the promotion and practice of lexicography that spans the entire Caribbean region. It is the successor to units that produced works such as the afore-mentioned Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (R. Allsopp 1996) and Caribbean Multilingual Dictionary (J. Allsopp 2003). It also is actively producing regional dictionaries such as a bilingual culinary dictionary of Caribbean English with Costa Rican Spanish, a multilingual dictionary of French Guianese Creole, and a multilingual dictionary of medicinal plants of the region. We are well-placed to assist with any projects in the French-official Caribbean, from design to research to execution of the final product. From the urgent projects of documenting the endangered varieties of St Barth and French Guiana to the longer-term projects of multilingual dictionaries and dictionaries of regionalisms in Standard French, the Allsopp Centre is eager to fully document the lexicons of the French-official Caribbean.

5 References

Alleyne, M. C. (1985). A Linguistic Perspective on the Caribbean. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center, Latin American Program.

Allsopp, J. (2003). The Caribbean Multilingual Dictionary of Flora, Fauna and Foods in English, French, French Creole and Spanish. Kingston: Arawak.

Allsopp, R. (1996). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aub-Buscher, G. (2003). Linguistic Paradoxes: French and Creole in the West Indian DOM at the Turn of the Century. The Francophone Caribbean Today: literature, language, culture. Gertud Aub-Buscher and Beverly Ormerod Noakes (eds). Mona: UWI Press. pp. 1-15

Barbotin, M. (1995). Dictionnaire du créole de Marie-Galante. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Barthelemi, G. (2007). Dictionnaire créole guyanais-français : suivi d’un index français-créole guyanais. Matoury, Guyane: Ibis Rouge Editions.

Bazerque, A. (1969). Le langage créole. Guadeloupe : ARTRA.

Bollée, A. (2000). Dictionnaire étymologique des créoles français de l’océan Indien. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag.

Breton, R. (1665). Dictionaire caraibe-françois: Meslé de quantité de remarques historiques pour l’esclaircissement de la langue. A Auxerre: Par Gilles Bouquet.

Bureau du Secrétaire d’Etat à l’Intégration des Personnes Handicapées (2014). Vers une meilleure compréhension de la langue des signes haïtienne. http://www.seiph.gouv.ht/vers-une-meilleure-comprehension-de-la-langue-des-signes-haitienne-2/. Accessed March 30, 2018.

Camargo, E. & Tom, I. Hakëne omijau eitop Dictionnaire bilingue Wajana-Palasisi Wayana-Français. Cayenne: CELIA/DRAC-Guyane/TEKUREMAI.

Cocote, E. (2017). Création d’un lexique bilingue français régional des Antilles-espagnol cubain, et enjeux traductifs et interculturels. PhD. thesis. Université des Antilles, Pointe-à-Pitre.

Confiant, R. (2001). Dictionnaire des néologismes créoles. Matoury, French Guiana: Ibis Rouge Editions.

Confiant, R. (2004). Le grand livre des proverbes créoles: Ti-pawol. Paris: Presses du Châtelet.

Confiant, R. (2007). Dictionnaire créole martiniquais-français. (2 vol.) Matoury, French Guiana: Ibis Rouge Editions.

Contout, A. (1992). Le petit dictionnaire de la Guyane : Classé par thèmes, avec histoires de mots, tournures et conversations. Cayenne: Self-published.

Crosbie, P., Frank, D., Leon, E. & Samuel P. (2001). Kweýol̀ Dictionary. Castries: Ministry of Education, Government of Saint Lucia.

Decker, K. (2004). Moribund English: The case of Gustavia English, St. Barthélemy. English World-Wide, 25, pp. 217-254.

Étienne, C. (2005). “Lexical particularities of French in the Haitian press: Readers’ perceptions and appropriation.” Journal of French Language Studies, 15 (3), pp. 257-277.

Fontaine, M. (1991). Dominica’s diksyonnè : Kwéyòl-Annglè = Dominica’s English-Creole dictionary. Roseau, Dominica: The Folk Research Institute, the Konmite Pou Etid Kweyol (KEK).

Grenand, F. (1989). Dictionnaire wayãpi-français, lexique français-wayãpi: Guyane française. Paris: Peeters-Selaf.

Hazaël-Massieux, M-C. (2002) A propos des dictionnaires créoles des Petites Antilles. http://creoles.free.fr/Cours/diaporamas/dictionnairescreoles.pps. Accessed March 30, 2018.

Jourdain, É. (1956). Le vocabulaire du parler créole de la Martinique. Paris: Klincksieck.

La Salle de L’Etang, Simon Philibert de (1763). Dictionnaire galibi: Présenté sous deux forms; I ̊ commençant par le mot françois; II ̊ par le mot galibi. Précédé d’un essai de grammaire. Paris: Chez Bauche.

Le Dû, J. & Brun-Trigaud, G. (2013). Atlas linguistique des Petites Antilles. Paris: CTHS.

Ludwig, R., Montbrand, D., Poullet, H., & Telchid, S. (1990). Dictionnaire Créole français : (Guadeloupe) : avec un abrégé de grammaire créole, un lexique français/créole, les comparaisons courantes, les locutions et plus de 1000 proverbes. [Paris?]: Servedit/Editions Jasor.

Maher, J. (2013). The Survival of People and Languages: Schooners, Goats and Cassava in St. Barthélemy, French West Indies. Leiden: Brill.

Maïs, J-L. (2002). Dictionnaire aluku tongo – français, français – aluku tongo. Toulouse: Sedrap.

Mondesir, J. E., & Carrington, L. D. (1992). Dictionary of St. Lucian Creole. Berlin; New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Patte, M. F. (2012). La langue arawak de Guyane: Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français arawak. Marseille: IRD Editions.

Pinalie, P. (1992). Dictionnaire élémentaire français-créole. Paris : L’Harmattan / Presse Universitaires Créoles.

Pinalie, P., & Confiant, R. (1994). Dictionnaire de proverbes créoles. Fort-de-France: Ed. Désormeaux.

Pompilus, P. (1958). Lexique créole-français, thèse complémentaire. PhD. thesis. Université de Paris, Paris.

Pury, S. de. (1999). “Le Père Breton par lui-même.” in M. Besada Paisa (ed.). Dictionnaire caraïbe-français. Paris: Karthala/IRD. pp. XV-XLV

Rickford, J. R. (1987). Dimensions of a Creole Continuum. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Siegel, J. F. (2009). Barthelemi, Georges. 2007. Dictionnaire créole guyanais-français : suivi d’un index français-créole guyanais and Confiant, Raphael. 2007. Dictionnaire créole martiniquais-français. (2 vol.), The French Review 83 (2). pp. 463-65.

Skybina, V. & Bytko, N. (2014). Caribbean creole lexicography as a cultural phenomenon. Paper presented at 20th Biennial Conference of the Society for Caribbean Linguistics (SCL) in conjunction with the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL) and the Associação de Crioulos de Base Lexical Portuguesa e Espanhola (ACBLPE), Aruba.

Telchid, S. (1997). Dictionnaire du français régional des Antilles: Guadeloupe, Martinique. Paris: Bonneton.

Tobler, Alfred W. (1987) Dicionário Crioulo Karipúna-Português/Português-Crioulo Karipúna. Brasilia: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Valdman, A., & Iskrova, I. (2007). Haitian Creole-English Bilingual Dictionary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, Creole Institute.

Valdman, A., Klingler, T. A., Marshall, M. M., & Rottet, K. J. (1998). Dictionary of Louisiana Creole. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Valdman, A., Moody, M. D., & Davies, T. E. (2017). English-Haitian Creole Bilingual Dictionary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Creole Institute.

[1] Alleyne (1985) criticizes the notion of “French-speaking Caribbean” (and similarly for “English-” and “Dutch-speaking”) because the people in this part of the world frequently do not speak French, but are likely monolingual in Creole.