Few have ever mastered the English language like Abraham Lincoln. From his days as a young, backwoods bibliophile to one of history’s most expressive writers, Lincoln’s love of language helps us understand not only the man, but all that he represents. How did Lincoln acquire his remarkable way with words? An eighteenth-century dictionary now in the Rare Book Collection at Louisiana State University sheds some light on the question.

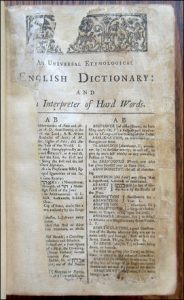

LSU’s copy of the 1770 edition of Nathan Bailey’s Universal Etymological English Dictionary was owned by Mordecai Lincoln, the future president’s uncle and one of the most influential figures in his early life. First published in 1721 and reissued many times over the next eighty years, Bailey’s dictionary was used throughout the English-speaking world, including the new state of Kentucky, where this copy came into Mordecai Lincoln’s possession at least as early as 1792.

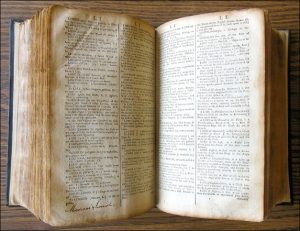

The volume raises interesting questions. Scrawled in the margins next to Bailey’s definitions of catfish and castanets are the words: “Mordecai Lincoln, his hand and pen, he will be good, but God knows when. When he is good, then you may say, the time is come and well hurray.” Thirty years later, the first part of this jovial rhyme shows up in a copybook, written in southern Indiana by a teenage Abraham Lincoln. The copybook may be the earliest surviving example of his writing. Scholars have been unsure whether Lincoln coined the rhyme himself or copied it from an unknown source. LSU’s copy of Bailey’s dictionary suggests that the phrase was being used as a penmanship exercise in the Lincoln family long before their most famous son repeated it.

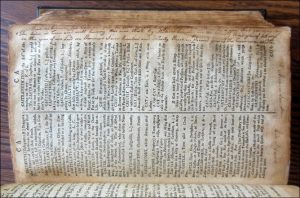

Mordecai Lincoln was clearly glad to own a copy of the dictionary. In addition to including his name in the verse mentioned above, he inscribed it in two other places: first on the page headed by the word unalterable, alongside the date “April 28, 1792,” then adjacent to a description of the English city of Lincoln. At the middle of a group of pages discolored by some kind of memento once stuck between them, we find the definition of the Hebrew name Mordecai (“Queen Esther’s guardian”).

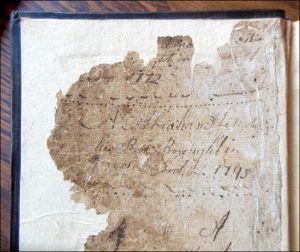

Most intriguing is the front endpaper. Though badly mutilated, it still bears the inscription “Abraham Lincoln, his book, brought [sic] in the year of our Lord 1795.” Above this inscription is another that has almost disappeared due to paper loss, but the date 1772 is still visible, as well as the partial word “Linc—,” presumably a sign that other Lincolns owned the book before Mordecai. Also inscribed on the page, and now nearly invisible, is the name Thomas. More research is needed to determine whether this was Thomas Lincoln, Mordecai’s brother and the president’s father.

The rhyming inscription and the fact that we know Abraham Lincoln read dictionaries in his youth has led several historians to believe this was one of the books that passed through his hands. Though he may have borrowed the book from his uncle, it is far more plausible that the “Abraham Lincoln” of the inscription is the president’s cousin, Mordecai’s son Abraham, who was born around 1795. Could the mysterious usage of the word brought refer to his birth—i.e., brought forth? The word has mistakenly been given as bought by historians. The original may be a simple misspelling by a novice penman, but no matter what it signifies, it is hard to see how it could apply to the president, who was not born until 1809.

Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge, author of a well-known 1928 biography of Lincoln, was the foremost advocate of a connection between Bailey’s dictionary and the erstwhile Hoosier. Beveridge knew about the volume through James A. McMillen, librarian at Washington University in St. Louis and later library director at LSU. McMillen claimed to have acquired the book from his aunt, who in 1879 found it in a Hancock County, Illinois, house formerly occupied by one of Lincoln’s cousins—or, some say, by “Honest Abe” himself. (Mordecai’s son Abraham died in Hancock County in 1852, more reason to believe the book belonged to him and not the president.) When we trace Beveridge’s footnotes, it is clear that he confused Bailey’s dictionary with James Barclay’s, a book the young Lincoln cherished. Yet writers on Lincoln have reproduced Beveridge’s error over the years.

LSU librarians have determined that this is the same copy of Bailey’s dictionary that Harry E. Barker, a Los Angeles book dealer, used to create “facsimiles” by transcribing the original Lincoln family inscriptions into other copies of Bailey’s dictionary, which, with no intent to deceive, he then sold as curiosities to collectors of Lincolniana. Two of Barker’s creations have been located, one at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and another in the Cordell Collection of Dictionaries at Indiana State University. Staff in both libraries were instrumental in researching this story.

Regardless of whether Lincoln ever read from his uncle’s copy of Bailey’s dictionary, it is a testimony to his legacy that so many have wanted this to be a tangible relic of his life. Even if it is not what some have claimed, the book does, in fact, advance our understanding of Lincoln. Though he was unusually bright, those around him were not all as suspicious of “book larnin’” as his father, Thomas, is supposed to have been. At least one other member of the Lincoln family, we can be sure, found a dictionary to be a valuable object. Did he simply use it to better understand the Bible, or did he have other aspirations? We may never know, but this small window into the world in which Lincoln grew up is a fascinating example of the kinds of questions scholars can raise by exploring rare books and their owners.

(Michael Taylor is Public Services Librarian at the Center for Southwest Research & Special Collections, University of New Mexico https://elibrary.unm.edu/cswr/. He was formerly the Curator of Rare Books at Louisiana State University. Eighteen years ago he developed an interest in rare books as an undergraduate working on the Cordell Collection with David Vancil.)