A number of those in our field have died recently. Thus this Newsletter has a special In Memoriam section. The remembrances are given in alphabetical order.

“Canada’s Word Lady”: Katherine Barber (1959-2021)

By Stefan Dollinger

On 24 April 2021, Katherine Patricia Mary Barber, grand dame of the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, passed away in Toronto at the hand of a particularly aggressive form of brain cancer. She was 61. Katherine leaves behind a profound legacy of reference works of Canadian English, big and small, and two well-made general-interest books on Canadian English. While her flagship reference work has not been maintained since 2008 [last ed. 2004] – in what I call an industry-wide problem below –, her Twitter account, @thewordlady, as well as her blog, katherinebarber.blogspot.com, act as her public record since then, which will be valuable for historians of Canadian intellectual life.

I met Katherine – Canada’s Word Lady, as she was stylized in the media – for the first time in 2007. She was a linguistic celebrity and at the peak of her game, commanding a capacity crowd of nine or ten dozen readers on a nation-wide book tour at Vancouver’s Public Library. The book to be promoted had the enticing title Six Words You Never Knew Had Something to Do with Pigs: And Other Fascinating Facts About the English Language. In it she did what she did best: explain complex linguistic scenarios with simple, accessible words, and a sprinkling of fun. I remember her “English squish-and-mush” rule, or the like, a name she used to synthesize the massive French influence on English before Chaucer’s time. Very funny, very effective, very correct. When I hypercritically reviewed her 2008 Only in Canada: You Say: A Treasury of Canadian Language, it was, not just for an academic review, profoundly appreciative as well.

At the VPL, Katherine – exceptionally smart, engaging, gracious, funny, quirky, kind, and full of surprises – was at her summit, but then again, her stellar light must have been already on the decline. After all, the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, the “CanOx”, as UBCers know it, had been a massive best seller, a cash cow, staying on the bestseller lists for years since publication in 1998. Little more than a year after the Vancouver talk, however, Katherine’s publisher would shut down the entire Canadian reference operation at Don Mills, Toronto: the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, its spin-off and school dictionaries, usage and spelling guides and let Katherine and her six lexicographical staff off. The publisher giveth, the publisher taketh.

After her talk she, the famous lexicographer, would take me, the recent postdoc, on a walk around the 10 km Stanley Park Seawall. Her company paid for the cab to the park and a snack. OUP Canada, I imagined, could afford such treats, as CanOx had been without competition for about a decade, a real monopolist, owed to Katherine’s PR savvy and networking skills, which were highlighted by many of her obituary writers. Katherine’s playful and joyful way to work the Canadian media outlets, defeated – on PR and marketing, not on scholarly standards – not two, but de facto three excellent desk dictionaries of Canadian English in what I once called the Great Canadian Dictionary War: the Gage Canadian (without taboo words), the ITP Nelson (with taboo words) and, even preventing publication at a late stage of a Fitzhenry Whiteside desk dictionary (see David Friend’s obituary of Fraser Sutherland in this issue).

About a decade after – in hindsight – destroying the financial basis of the entire competition in the moderately-sized Canadian English reference market – a market created by W. J. Gage Ltd. since the 1950s –, the CanOx would be shut down by her English publisher. It didn’t make enough money. A business move, no doubt, likely motivated by high costs (e.g. 1991-1998: only costs, including staff, but no dictionary and therefore no sales; as of 2005: a slumping paper dictionary market). Despite assurances, 13 years on and we haven’t seen an update, however minor, of the CanOx “from England”, as claimed in 2008.

The headline of Katherine’s obituary in the New York Times reads that she “defined Canadian English”. What an appropriate appreciation. Right here, however, we have the one trope that can be considered a problem in a private, enterprise-driven Canadian English publishing industry: a tendency, owed less to Katherine’s preference but to unwritten rules of the game, to short-change those on whose work she was able to flourish. There were many: companies – Gage Ltd, Nelson Inc –, scholars, Walter S. Avis (obituary in World Englishes Vol. 1, 1980), C. J. Lovell (Canadian Journal of Linguistics 1960), P. D. Drysdale (Canadian Journal of Linguistics 2021) and Matthew H. Scargill (Globe & Mail, 20 Aug. 1997), and lexicographers, such as T. K. Pratt or Gaelan Dodds de Wolf (all of Gage Ltd/Nelson Inc).

Short changing is usually owed to business pressures and the need for PR, company-loyal PR, that other scholars-turned-lexicographers have critiqued (e.g. T. K. Pratt). When the Globe & Mail, for instance, quotes Katherine as saying that “We had almost no Canadian primary research to rely on,” from a 2005 text, Katherine either had unrealistic expectations of the kind of studies she’d find, or she took for granted the 60 years of research that she built on. That work included then recent and exciting findings by top-notch linguists J. K. Chambers and Charles Boberg on words in Canadian English – the very thing she was studying (see the the 2019 history of lexicography, Creating Canadian English with Cambridge UP).

That something has – structurally – been not quite right with the English-language reference publishing can be surmised by Katherine’s decision to carve an entirely new career for herself after CanOx was mothballed. That she guided international ballet tours with her own company speaks to her passion, conviction, dedication and persuasion skills, offering a new kind of high brow tourism. Perhaps she enjoyed, post-2008, more time with her choirs, which she attended with at least another profound language expert, professor Carol Percy. That passion of hers, choral singing, it is claimed in Creating Canadian English, can be detected in Katherine’s lexicographical work. Katherine, for instance, adapting the Concise Oxford Dictionary’s entry in her work towards CanOx-1 (1998), put hand to take up. Meaning #6 was added and defined as ‘join in (a song, a chorus etc.)’. Coincidence? Hardly.

Meaning #9 of take up, however, was also added, ‘go over the correct answers to (homework, an assignment, a test, etc.)’ in what we now know is an expanding Canadianism. Katherine, lacking a connection to academic research programs of usage in Canada (which were – and are still – rare, underfunded, or student-led initiatives) could not really know that at the time. So, while she – correctly and remarkably – added meaning #9 to the raw text she worked from (the 8th edition of the Concise), she did, in a puzzling move, not label it “Cdn.”; in neither of the two CanOx editions. Since quite a few words were bestowed with the label “Cdn.” in her dictionaries, some that do not deserve that appellation by any stretch of the imagination (also in Creating Canadian English), we have a remarkable situation that can best be explained socially: with almost the entire CanOx team hailing from the “core area” of take up #9 (SW Ontario and NW Manitoba), they used it the expression natively but had no clue it was Canadian. Take up #9, and this is the punchline, is likely representative of a big chunk of Canadian English awaiting discovery. In other words, there is still plenty of work to do.

Katherine’s career – its lexicographic rise and fall – suggests that dictionaries should be considered essential services. Just as we should not sell our infrastructure, roads, harbours and internet nodes to offshore investors, we should not outsource our key dictionaries, not even to “friendly” companies. These companies inevitably have their own goals and will pull the plug on “foreign” products more quickly than their own. Katherine was in the midst of all of this. The ultimate fault, however, cannot be with a foreign publisher – that, after all, trained Katherine before she started on a dictionary that, for seven years, only cost money. So much that even the absolute Canadian bestseller would not turn a lasting profit in a shrinking paper market. OUP was just doing their business job and doing it well.

Fault must be placed, fair and square, with an academic linguistics that has belittled for half a century the needs of speakers, writers, the business world and everyone else for their own hunt of the holy grail: the more abstract, the better, the less practical, the sweeter. In a strange twist of affairs, this linguistics has been letting down both the average mainstream English user and the First Nations in Canada. How so? For the latter, how can another PhD on X-Bar Theory assist the dying language it uses as “data”? The former, for the following fact: when OUP came asking in 1991 there was, in the entire country, as T.K. Pratt confirms, not one linguist who would want or be able to run OUP’s new flagship Canadian dictionary. How is that possible?

Then came Katherine Barber. She had a BA in French from Winnipeg, an MA in French from Ottawa, an experience as a research assistant with The Canadian Bilingual [i.e. English-French] Dictionary and knew the country. Her crucial meeting was on Prince Edward Island, a key place of Canadian Confederation, a key place for Canadian lexicography. Even better, perhaps, that she was born in England. OUP hired Katherine, trained her and put her in the driver’s seat of CanOx in a remarkable story of an originally low-profile David commandeering a Goliath project, from 1991 until it was over in 2008. They had a good run, one could say. In 2005, incidentally, the situation was unchanged, when I became editor of www.dchp.ca/dchp2. Again, after no Canadian faculty in Language or Linguistics, and no PhD student from the academic family compact, would touch it. Many years earlier, Lovell, who started the most profound Canadian lexicographical tradition that made Katherine’s work possible, was American and would, like Katherine, also die quite young. Treat your immigrants well!

Public perception has it that an Oxford dictionary must be so much better than one from Gage, Nelson, or Fitzhenry-Whiteside. That is, of course, nonsense. Katherine knew that but was not allowed to publicly say so. And why bite the hand that feeds you? It was a beautiful symbiosis while it lasted. I imagine, however, what the lexicographic world would have looked like without legal clauses, constraints and business secrecy, a world in which collaboration is built into company philosophy for better dictionaries rather than the one-directional goal of better profits at the expense of everything else. As every Canadian writer, editor, journalist – in short: person of letters – will tell you, who now has to make do without resource #1, a reliable, up-to-date dictionary (in app format or, alternatively, on paper as print-on-demand): that’s a mighty high price to pay for private business successes.

Imagine what a new collaborative Canadian dictionary, in Katherine’s memory, might be able to achieve today. As her nephew tweeted: “She expressed profound satisfaction at having contributed to the cultural life of this country, having literally defined the language we speak.” For about a decade and a half, Katherine was the go-to person. Imagine how excited she would be for an adequately funded national research unit that would produce a born-digital dictionary. Tax dollars can be spent much worse. I think this time around we would stick all our heads together in a country that is too big to be covered by one company alone and is too small for us all not to realize that we are all playing on the same team

During her time at OUP, Katherine developed into a formidable force, though she too, had to operate in this suboptimal model, much like the OED’s early Murray or Burchfield. On Oct. 8, 2020, Katherine retweeted a message by @CanE_Lab in what seems to be her last tweet: “@thewordlady discovered this one. #CdnWrdoWk #87 is a really slangy one: Molson muscle ‘beer belly’. …”. Late academic recognition, however informal, for one of the best Canadian word sleuths: Katherine will be sorely missed – the ballet aficionado, pastry baker (including the internationally unknown Linzer Torte), choir singer, cat lover and lexicographer extraordinaire – as she takes her place, I imagine, in the gallery of spokespeople for English Canada’s linguistic autonomy, next to Lovell (1907-1960), Avis (1919-1979), Scargill (1916-1997), Sutherland (1946-2021) and Drysdale (1929-2020).

Remembering Ronald R. Butters: February 11, 1940 – April 6, 2021

By Edward Finegan

After fighting the disease for several years, Ronald Butters lost his battle to cancer at age 81. Ron was a life member of the Dictionary Society of North America and a regular attendee at its biennial meetings. Among many contributions to the Society, he organized the 2003 biennial meeting at Duke University, where he spent his entire career as a faculty member and administrator. While Ron was also well known in other organizations, including the American Dialect Society and the International Association of Forensic Linguists, both of which he served as president, here I focus on his involvement in DSNA and on his dictionary and lexicographical work, which were intimately tied to his research into American English and to his engagement with forensic linguistics.

After completing a Ph.D. in English at the University of Iowa, Ron started as an assistant professor at Duke University in 1967 and retired from Duke in 2007 as Professor Emeritus of Linguistics and Cultural Anthropology. Over the course of four decades he chaired Duke’s English Department and Duke’s Linguistics Program for several terms each. He also co-chaired the North Carolina State University-Duke University Doctoral Program in English Sociolinguistics for eight years. At various times, he taught as a visitor at the University of Bamberg, Cadi Ayyad University, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and the International Summer School in Forensic Linguistics. In editorial capacities he served as editor of American Speech from 1996 to 2007 and as co-editor of The International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law from 2007 to 2010.

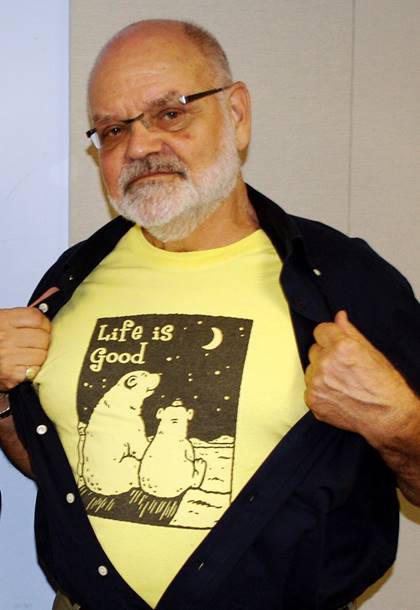

Ron was an active DSNA member and most recently presented a paper on “Fire Cider” at the Bloomington biennial in 2019; and on “Killer Tomato” at the Barbados biennial in 2017. But he also presented a paper on “Down on the pharm: ‘Convenience’ abbreviations in authoritative dictionaries” in Athens in 2013; on “‘Chocolate chip’ and the silent subreption of the lexicon: A forensic linguist at work” in Montreal in 2011; on “A harmless drudge at work: The thoroughly tedious etymology of crack ‘smokable cocaine’” in Bloomington in 2009; on “‘Legal evidence and lexicographical methodology: Life’s Good” in Chicago in 2007; and on “The dictionary treatment of similatives” in Boston in 2005 (with Sarah Hilliard). He gave papers as well at the DSNA meetings in Cleveland in 1995 and Madison in 1997. With Margaret Wolfram, Ron co-organized the 2003 biennial at Duke, and at the meeting Jennifer Westerhaus (now Jennifer Adams) and Ron jointly presented a paper on “Trademark, metaphor, and synecdoche in dictionary labeling.” Ron also published prolifically, including several major contributions to Dictionaries – in 1998, “Cary Grant and the emergence of gay ‘homosexual’; in 2001, “We didn’t realize that lite beer was supposed to suck!”: The putative vulgarity of ‘X sucks’ in American English”; and in 2015, “Using lexicographical methodology in trademark litigation: Analyzing similatives.” He also attended other DSNA meetings, including the Vancouver biennial in 2015, but I haven’t been able to document his giving a paper there.

Ron’s connection to dictionaries wasn’t only as a scholar. Starting in 1999 he served as an Editorial Advisory Board member for the New Oxford American Dictionary and as NOAD’s expert advisor on vulgar terms and terms relating to homosexuality. According to a declaration he filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office in support of registering DYKES ON BIKES as a trademark, Ron reported that he “personally read, revised as necessary, and passed final judgment on the definitions given for such terms, including the entry for dyke.” That experience, that credential, gave him notable street cred, and the USPTO, after previously rejecting the application, changed its mind and issued a registration for DYKES ON BIKES.

Over the decades that encompassed our colleagueship and friendship, Ron was totally at home in his own skin. To illustrate the point, I cite but one amusing story (aspects of which I can confirm personally). When the American Name Society met alongside the American Dialect Society and the Linguistic Society of America in Oakland, California in 2005, Ron chaired an ANS session called “Queer Names of Stage, Screen and Fiction,” and he presented the session’s first paper – on “Names in queer novels before Stonewall” (Mr. Right and Deli Pickup, among them). Following his talk, North Carolina State University grad student Phillip Carter spoke on “The social meaning of drag queen names.” For an awkward moment once chairperson Ron opened the Q&A following Carter’s talk, the room fell silent. Breaking the silence himself, Ron puckishly asked Carter for his drag name! Carter blushed, I’m told (my memory fails me on that detail), but when Ron followed up by announcing “for the record” that his was Cocoa Butters, he conveyed a striking easiness with the humanity of his gesture and made possible a lively discussion following an awkward inquiry. (See Harmanci 2005.) The incident highlights something at the heart of Ron’s gift to be himself and simultaneously challenging, on the one hand, and put people at ease, on the other.

While Ron was generous and deeply, personally caring, he could also be quite critical, sometimes seemingly without realizing how his criticism might sting. When Cambridge University Press published Language in the USA: Themes for the Twenty-first Century, a collection of some 26 chapters edited by John Rickford and me, it wouldn’t have been straightforward for journal editors to identify knowledgeable reviewers who hadn’t contributed a chapter. In inviting contributors, Rickford and I had various constraints to honor and balances to strike, and while we sought Ron’s valued advice on some matters, we did not invite him to contribute a chapter. Thus free to assess the volume, his published review in Language pulled no punches, especially in discussing the chapters that he saw as insufficiently thought-through on politically and socially sensitive issues like language preservation (Butters 2007). Similarly, as president of the International Association of Forensic Linguists, his 2011 presidential address took aim at the work of some forensic linguists, two in particular whom he named, thus prompting the editors of the proceedings, which included a revised and modulated version of the address, to invite a notably fair-minded scholar (and former IAFL president himself) to contribute a concluding chapter to the volume, a paper that had not been presented at the meeting and seems intended in part to salve feelings. In one of those academic workarounds that a collegial atmosphere dictates and that makes one envious for its subtlety, the editors wrote this about the concluding chapter they had invited to balance Ron’s address: “To commemorate Butters’ term as the President of the IAFL, Larry Solan kindly accepted an invitation to write a response to the plenary address, which we include in these pages as a way to stimulate discussion in an area close to Ron’s heart.” (See Tomblin et al., eds. 2012: 8.)

Also close to Ron’s heart was the matter of ethics in scholarly and professional publishing and in the practice of forensic linguistics, and he was centrally influential in moving several organizations to adopt codes of practice. (See, e.g., Butters 2009.)

Bigger than life he was, and Ron will be missed. Besides his colleagues at Duke, in the American Dialect Society, the International Association of Forensic Linguists, DSNA, and other organizations, Ron is survived by his two daughters, Rachel Willis and Catherine Blum, and his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He also leaves behind Stewart Campbell Aycock, his husband and, for many years before they were able legally to marry, his beloved partner.

References

Butters, Ronald R. 2007. Review of Language in the USA: Themes for the Twenty-first Century. Ed. by Edward Finegan and John R. Rickford. Language 83 (3): 883-886.

Butters, Ronald R. 2009. The forensic linguist’s professional credentials. International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law 16 (2): 237-252.

Harmanci, Reyhan. 2005. Name games/The semantics of sexuality. SFGATE. Available at www.sfgate.com/living/article/NAME-GAMES-The-semantics-of-sexuality-2703404.php [accessed Aug. 6, 2021].

Tomblin, Samuel, Nicci MacLeod, Rui Sousa-Silva, and Malcolm Coulthard, eds. 2012. Editors’ introduction. Proceedings of the International Association of Forensic Linguists’ Tenth Biennial Conference. Birmingham, UK: Centre for Forensic Linguistics, Aston University.

Patrick Drysdale

By Victoria Neufeldt and Stefan Dollinger

Patrick Docker Drysdale, a charter member of the DSNA, died December 9, 2020 in hospital in Oxford, England, after a brief illness. He was 91 years old. From the beginnings of our Society, Paddy, as he was known, was a strong supporter of the idea of a formal organization representing the still little-known field of lexicography. When the original 24 members (the Founding Members) sent out news of the new society after the founding meeting in 1975 and invited people to join, he signed up right away and invited his dictionary editors to join as well. He attended the first official meeting of DSNA in 1977 and was a regular participant in meetings until he and his wife, Olwen, returned to England in 1982.

Paddy was born in the county of Shropshire, England on July 9th, 1929. His family roots were in the village of Radley, in Oxfordshire, where he returned when he went back to England. There he continued his involvement with the DSNA and with lexicography on a part-time basis for some years, often serving as a consultant on Canadian English, but he also returned to earlier preoccupations, theatre and history, and with Olwen was able to indulge a lifelong love of travel. He became an expert on the history of the Radley district, writing two well-regarded books on the area.

He maintained his strong interest in theatre from his early youth, that found its expression in stage managing and later in writing plays. He was particularly fascinated by the mediaeval period and the legends of King Arthur.

His contribution to Canadian lexicography is seminal. By good luck, he came in at the start of the first major Canadian lexicographic venture in English. He had come to Canada from his native England in 1955, working in St. John’s, Newfoundland as the stage manager of an English theatre company. He left that work the following year and took a position in academe, as an assistant professor of English at Memorial University. This put him in position, in 1958, to catch the eye of the leadership of the educational publisher W.J. Gage Inc. in Toronto, who had just committed the company to publishing a series of three graded dictionaries of Canadian English for schools and also to creating and producing a dictionary of Canadianisms on historical principles from scratch. This was a huge commitment for a relatively small commercial publisher in Canada and Paddy was offered the job of overseeing these projects. He took it on in 1959 and made history. The three school dictionaries in the Dictionary of Canadian English series plus the Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles (DCHP) collectively “succeeded in bringing Canadian English into print, and, more importantly, into our consiousness” (J.K. Chambers, 2019). Paddy had accepted the job “almost on a whim”, he said [footnote: personal conversation with Prof. Stefan Dollinger, 2017], relocating with Olwen to Toronto, trading both the theatre and academe for what became an equally strong, long-term professional investment in lexicography.

The three school dictionaries were based on the Scott-Foresman school dictionaries, by agreement with that publisher. Academic Canadian linguists were engaged to thoroughly revise the dictionaries for use by their intended Canadian audience. This involved research into actual Canadian usage like it had not happened before, including pronunciation, spelling, vocabulary, and social and cultural preferences. The new dictionaries were completed and published in succession, in 1962 (The Beginning Dictionary), 1964 (The Intermediate Dictionary), and 1967 (The Senior Dictionary). Work on the DCHP was going on at the same time, involving some of the same scholars, particularly Walter S. Avis. So for the period 1959 to 1967, Paddy was always juggling at least two projects at the same time and also overseeing the gathering of citations (examples of actual usage in context). It is astonishing that so much was accomplished with basically one in-house person holding it all together.

DSNA was pivotal in involving Paddy in the last production stages of DCHP-2, in 2017, as one DSNA member knew where Paddy was located and got in touch with him for the new editorial team. Graciously, Paddy wrote a nice foreword, linking the 1967 edition to the 2017 edition. The following year, when preparations were being made for a history of lexicography in English Canada (appeared with Cambridge University Press in 2019 as Creating Canadian English: the Professor, the Mountaineer, and a National Variety of English), Paddy invited the chief editor of DCHP-2, Stefan Dollinger, for an afternoon at his estate in Radley. He and Olwen were reliable witnesses of that first generation of lexicographers of the 1950s and 1960s that is now, with Paddy’s passing, no longer with us.

An appropriate descriptor for Paddy in his contribution to the publication of the original four Gage dictionaries would be ‘linchpin’. He was the one who coordinated everything that came in and went out in the course of the creation of these dictionaries; he was the in-house coordinating editor, a crucial position in a complicated endeavour such as this, involving academic researchers, writers, editors, and in-house production people. All this was in the era of paper, paste-ups, typewriters, mountains of handwritten notes, and hot metal. Paddy was the ideal person for this work, not just because of his love for and understanding of Canadian English and the “art and craft of lexicography”, to quote Sidney Landau, as well as the whole production process involved in publishing books, but also for the kind of person he was: unfailingly, quietly courteous, friendly, and unassuming. He was also completely unflappable — a precious quality in the milieu in which he worked.

Paddy stayed on after 1967, of course, through major revisions of all three school dictionaries in the 1970s and early 1980s, including a significant expansion of the “Senior” volume into the Gage Canadian Dictionary, for use as a general desk dictionary. The GCD was published in 1983, a year after Paddy left Gage, but he was the initiator of that project too. His legacy circle is complete.

–Victoria Neufeldt is an “alumna” of Gage Publishing. She was hired by Paddy Drysdale in September 1973 to work on proposed major revisions of the school dictionaries. She remained on staff after Paddy left in 1982, continuing her work with the Dictionary of Canadian English series, till the end of 1983.

–Stefan Dollinger is Professor of English Linguistics at UBC Vancouver, chief editor of DCHP-2, www.dchp.ca/dchp2. Stefan is also a consultant for the Österreichisches Wörterbuch, 44th ed., 2022 (Austrian German Dictionary) and researches standard language varieties from a pluricentric angle.

Fraser Sutherland (1946-2021)

By David Friend

Fraser Sutherland was a man of letters. That expression is used less frequently now than in the past – more about that later – but it’s a good shorthand for describing the range of his achievements. Fraser was first of all a poet, but he made notable contributions to Canada’s literary culture in many ways for several decades. At different times he was a journalist, an editor, a critic, a writer, a teacher and mentor…and a lexicographer. There are several remembrances of Fraser to be found online, written by people who knew him well and admired him. They are worth seeking out.

The purpose of this particular memoriam is to recognize and appreciate Fraser as a lexicographer. He did the bulk of his lexicographical work in the 1990s, a heyday of dictionary making in Canada. During this time, simultaneously, several publishers decided to create “authoritative” dictionaries that would catalogue, encode, celebrate, and profit from Canadian English. Fraser was the lead on one of those projects – he was the editor of a Fitzhenry & Whiteside general-purpose dictionary, meant to be an expanded and more fully “Canadian” version of their Funk & Wagnalls Canadian College Dictionary. Unfortunately, Oxford’s well-publicized entry into the field killed the new Fitzhenry & Whiteside venture before publication, even though by then Fraser had done a substantial amount of research and definition writing.

Abruptly untethered from that project, Fraser brought his expertise to Nelson, which was also undertaking a major Canadian dictionary. He worked specifically on new Canadian terms and senses, providing both research and completed definitions. Very likely he had done most of that work already and was simply shifting it to this new context. I was one of those Nelson editors who refined Fraser’s work, bringing it in line with our Nelson conventions. It was immediately obvious to all of us that Fraser knew what he was doing. His definitions were deft, economical, clever. They did justice to the citations that accompanied them. We trusted his touch.

Others who worked with Fraser had a similar impression of him. Jan Harkness, who managed Nelson’s dictionary, remembers him this way: “Fraser was an indispensable contributor to the development of the Nelson Canadian Dictionary. Not only a deep repository of Canadian words and phrases, which he defined so aptly with grace and ease, Fraser had an extensive knowledge of the usage, history, and development of the English language in Canada. Fraser was an authoritative voice, a true scholar, and a good-humoured man.”

In the early 1990s, Fraser drafted new entries and definitions for the Gage Canadian Intermediate Dictionary. According to Gage’s Lexicographer, Debbie Sawczak, “Fraser worked freelance, drafting new entries and definitions, and I edited them—thinking to myself, This guy is a more experienced lexicographer than I am, and I’m editing him?! He may not have been much more experienced than I, but his work seemed quite polished to me. I remember him being easy to work with, although I don’t think we actually met face to face over the project. I first met him in person in 1998, after both the Canadian Oxford Dictionary and the Nelson Canadian Dictionary had come out; there was a panel discussion featuring Katherine Barber of Oxford, Fraser, who had worked on the Nelson dictionary, and myself. The three Canadian dictionaries were fierce competitors, of course, but because Fraser and I had already worked together and were familiar with each other’s skill, there was camaraderie and a sense of alliance rather than oneupmanship. I found him to be a friendly, intelligent, and humble guy.”

As late as 2015 Fraser still had connections with Canadian lexicography. Students who chatted with him then, at the DSNA-20 & SHEL-9 Conference in Vancouver, found him hilarious and remarkable…with a flair for cursing. But according to Stefan Dollinger, those same students noted that some of Fraser’s views – not about lexicography, but about the world – were not in sync with the times. This detail is worth including because it is an apt segue to this observation from Fraser himself, found in his 1998 review of the Canadian Oxford Dictionary: “Lexicographers like to believe they are dispassionate scientific recorders of current pronunciation, spelling, meaning and usage. But they underestimate the amount of prejudice, taste and judgment that is always involved.” The shifting over time of prejudices, tastes, and judgments is one of the reasons why dictionaries continuously need to be checked and renewed. Fraser’s observation is a lesson that points in many directions, to all those who curate words and try to represent their meanings, old hands and students alike.

Now, back around to “man of letters.” Google Books Ngram Viewer says that the expression has been steadily in decline from a peak around 1900. It’s an old-school word, for obvious reasons. When Fraser worked on dictionaries and other reference books, Google Ngram Viewer didn’t exist. The online universe was smaller, slower to move around in. Most of us doing lexicography in Canada had no access to corpora. It was a different time. Old school. Fraser came to lexicography in that era. Although I had many amiable conversations with Fraser about words, definitions, and Canadian English, I never asked him how he started with lexicography and how he became so skilled. Did someone teach him? What resources did he have at his side? How did he evolve his methods? All unknown. I regret that I never asked him those questions.

After the Nelson project, Fraser was involved with many other reference works. Because he was reliable and worked quickly, he was a go-to freelancer. Very, very few lexicographers gain anything like a public profile, and there’s not much of a record of the contribution Fraser made to the documentation and definition of Canadian English. Probably he had a bigger impact than we know.

Lexicographers, no matter what discipline they come from, love language. That was certainly true in Fraser’s case. Definition writing is a blend of analysis, precision, intuition, and art. Fraser was very good at it. So I’d like to give the last word to Fraser himself, in which he defines (or at least describes) himself as a poet. Here is the sound of his voice, as preserved in the virtual pages of Encyclopedia.com: “Whether I have written them or not, the poems I would like to write would have the beauty, autonomy, and otherness of a bird, beast, or tree. When I review what I have done, however, it is like reading the work of an eccentric, half-familiar stranger.”

Hanna Schonthal

By Joseph Pickett

It is with deep sadness that I report the passing of Hanna Schonthal, fine lexicographer and esteemed colleague. She was 62.

A native New Yorker, Hanna began her career in publishing working as a copyeditor, and then quickly established herself as a lexicographer, working on the International Dictionary of Medicine and Biology (New York: John Wiley, 1986) under the leadership of Sidney Landau.

Hanna then moved to Boston and entered into a long relationship with Houghton Mifflin (later Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) making significant contributions to the Third (1992), Fourth (2000), and Fifth (iterations after 2011) Editions of The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, and to many other books. Hanna primarily edited medical and life science entries, but her cosmopolitan background and her familiarity with multiple cultures (she was adept in several languages besides English) enabled her to enrich general vocabulary entries and language notes.

Over the years she served as an editor on many other dictionaries published by Houghton Mifflin, such as various college editions, science dictionaries, dictionaries for children and students. She had the lead role as project editor of the first edition of The American Heritage Children’s Science Dictionary (2003).

Highly intelligent and widely read, Hanna was an adept definer and had superb editorial judgment. She helped shape the character of all the books she worked on, and her wittiness and wry sense of humor leavened the spirits of everyone she collaborated with.

Lexicography was only one of her multiple careers. A determinedly independent and private person, she commanded several different professions, sometimes working full-time at one or another job and sometimes working multiple part-time jobs simultaneously. She worked for many years as a physical therapist and enjoyed seeing the immediate benefit that her skills gave to her clients (a feeling quite removed from her work as a dictionary maker). She also worked as a science writer, primarily for pharmaceutical companies (where the pay far exceeded that of her dictionary work). Somewhere in this mix, she hired on as a curriculum editor for WGBH. And as if all of this were not enough, later in her life she earned a certificate in teaching English as a second language and enlisted her love of language in the service of her students.

She was, in short, a remarkable woman, and I, like many other people, am proud to have known her.

P. K. Saha

The Society has learned that former member P. K. Saha passed away on August 10, 2021. PK’s article on “Dictionary Definitions of Linguistic Terms” appeared in the 1994 issue of Dictionaries. An obituary may be found at

https://obits.cleveland.com/us/obituaries/cleveland/name/prosanta-saha-obituary?pid=199806938 .”