Collecting Column for the Newsletter

David Vancil

Linda Mitchell was planning to write another piece in this issue on a wordbook-rich collection she has made use of, but having to prepare online classes for fall classes (she teaches at San Jose State University) is taking up her time and energy.

With the loss of Madeline Kripke, we are experiencing not only a sadness at her death but the uncertainty of knowing what will happen to the physical manifestation of legacy—her thousands of dictionaries and other works of interest to DSNA members. What will happen to her wonderful books? She had considered for many years what should be done with them. But she was brought down by COVID-19 without having made any concrete plans, as far is known. Let’s hope for the best.

I recall in conversations with Tom Rodgers, who focused on books lacking in the Cordell Collection, that he was contemplating donating his collection to a university, in particular Emory University. Tom was an entrepreneur who could have devised a plan that was advantageous to his survivors and researchers alike. But he suffered a swiftly moving health crisis that left him dead within a few months in April 2012 with no time or energy to follow through.

Nonetheless, many named collectors have managed to safeguard their legacies by placing their dictionary collections in the hands of institutions of higher learning. In many cases, these have ended up being useful to scholars, as my 2011 Dictionaries article on seven such collections in North America indicates. That article is out of date and could easily be expanded to include institutions with similarly significant holdings, such as the Library of Congress.

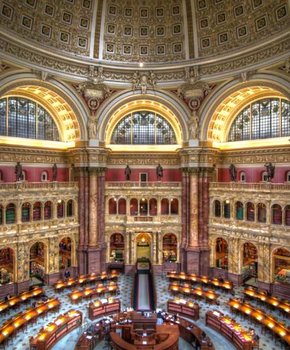

Speaking of the Library of Congress, I recall visiting it in the early 1990s along with other sights and again in 2018 after the March for Our Lives, in which we found ourselves participants. What a change. Washington had become not a spectacle for the few but a destination for the many. It’s possible that many of the people who attended the March stayed afterwards to contribute to the size of the crowds at monuments and museums during our stay, but having experienced burgeoning crowds in other travels, I was expecting to experience crowds in Washington as well. However, I wasn’t prepared for what I encountered at the Library of Congress. The number of people making its way into the Thomas Jefferson Building, with its ornate decorations, was almost stupefying. I am not used to a library as a significant tourist attraction. There were thousands of people milling around or taking tours, both self-guided and in groups.

My family and I entered through a tunnel stretching from our congressman’s office in the Capitol into a huge courtyard. We were issued tickets, as if to a sporting event. Of course, the Thomas Jefferson Building, one of several buildings comprising LC, is an architectural marvel. Who could really contemplate them, though? Their environs were swamped with tourists, sometimes jostling one another. The public area of the library was packed with humans. We did manage to eavesdrop on a few guides, as we snaked our way through the crowd, so I was able to glance through a small window into the rotunda below, where I gazed on the dictionary and encyclopedia alcove. It housed real books, not databases. Alas, I think there was only one researcher in the whole place.

One wonders what kind of impact this kind of tourism will exert on publicly accessible seats of higher learning. Will private institutions be compelled as well to open their doors to the curious? What safe haven will there be for scholars and collections?

Stay safe.