In DSNA news, this fall we have an update from Ed Finegan about our journal, requests from Steve Kleinedler and Stefan Dollinger, a report on the most recent MetroLex, and an obituary for one of our earliest members.

Update on Dictionaries

Ed Finegan, Editor, Dictionaries

In the Spring 2017 issue of the Society’s Newsletter, I reported that our journal would be moving to two issues a year in 2017, and we successfully did that, with the help of two associate editors (Orion Montoya and Sarah Ogilvie) and a new reviews editor (Traci Nagle). Volume 38 contained four articles (including the second installment of the history of the early years of the Society, written by Michael Adams), five Reference Works in Progress reports, and seven book reviews. The first issue of volume 39 will be mailed in August—a special issue treating problems of chronology in historical lexicography and lexicology (and with something of interest for all DSNA members in its ten articles—see the ToC below). The second issue of volume 39 will be mailed in the late Fall and will contain articles, reviews, and RWiPs.

Confessions of the Antedater by Fred R. Shapiro; Dating and Chronology in the Lexicology of Mormon English by A. Arwen Taylor and Kjerste Christensen; “Among the New Words”: The Prospects and Challenges of Short-Term Historical Lexicography by Benjamin Zimmer and Charles E. Carson; Periodization in Historical Lexicography Revisited by Michael Adams; Drifting in Timeless Polysemy: Problems of Chronology in Sanskrit Lexicography by Ligeia Lugli; History in Lexicography and Lexicography in History: A Reappraisal by Mirosława Podhajecka; Toward a Feminist Historiography of Lexicography by Lindsay Rose Russell; Histories in Translation: Antonio de Nebrija, Conceptions of the Past, and Early Modern Global Lexicography by Byron Ellsworth Hamann; Designing Green’s Dictionary of Slang Online by David P. Kendal; and an Introduction by Michael Adams.

As Dictionaries moves forward, the plan is for one issue a year to be devoted, at least in part, to a special topic. A CFP for papers on the topic of Vernacular Lexicography will be issued soon, and there are plans as well for a special issue on children’s dictionaries. Keep an eye peeled!

Honorary Presidential Memberships for 2018: Call for Nominations

Honorary Presidential Memberships recognize outstanding professional lexicographers and lexicologists early in their careers by awarding four-year memberships to the DSNA. Additionally, for the first DSNA conference that a recipient attends during this four-year period, $400 will be awarded to help defray the cost.

Members of the Society are encouraged to nominate graduate students or professional lexicographers in the first five years of their careers for Presidential Memberships. Please send letters of nomination to Steve Kleinedler at dsna.stevekl@gmail.com. In the Subject line, please put “Honorary Presidential Membership Nomination:” followed by the last name of the nominee. Letters should explain nominees’ lexicographical or lexicological interests, relevant activity and accomplishments, how sponsors see their nominees developing professionally, and why nominees should be members of the DSNA, in terms of both what the DSNA can do for the nominee, and what the nominee can do for the DSNA.

Please send nomination emails by September 30, 2018. Presidential Members will choose Founding Members or Fellows of the Society as their namesakes: so, a successful nominee might be, for instance, the Frederic G. Cassidy Presidential Member of the Dictionary Society of North America, if they so choose. Help us identify and recognize the next generation of DSNA’s leaders today!

Membership Committee

Dear Colleagues,

Earlier this year, the DSNA Executive voted to install a Membership Committee, for which I have taken the pro-tem lead.

We have seen in last year’s (very successful) attempt by David Jost (thanks a lot!) that a more active outreach is crucial for a healthy membership count. In this next phase, we would like to expand our efforts and attract new groups of potential members, for which I’d like to form a committee of 4-6 people that will report to the Board. If you’re interested in helping to decide, via the character of its membership so to speak, where DSNA will be heading, please be in touch. There are some ideas, but nothing is set in stone at all and I hope, very much indeed, that you will bring your own ideas to the table. Think: “DSNA in the 21st century? What do you need to do to stay/become (more) relevant?”

Please contact me if interested at stefan dot dollinger at u b c dot c a.

Stefan

CALL FOR PAPERS

Vernacular Practices of Lexicography

Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America invites submissions for a special issue focused on practices of lexicography arising outside of professionalized or scholarly dictionary-making. Other disciplines describe as “vernacular” the everyday practices and products that coexist (and may preexist) alongside officially codified and valorized practices. Scant research addresses the topic even though, on the scale of human linguistic history, most “practices of lexicography” have taken place outside the context of professional lexicography.

What are practices of lexicography?

- Explanations of meaning, in formal definitions or by other, pretheoretical strategies

- Glosses

- Organization of words into alphabetical, thematic, or other lists

- Thematic or schematic arrangements of concepts (thesauruses, ontologies; alignment-chart memes, Venn diagram memes)

- Division of word meanings into senses and methods of indicating multiple senses

What is vernacular lexicography?

Most, if not all, of what happens on Wiktionary and Urban Dictionary; digital, crowdsourced, and other electronically mediated community dictionary projects; glossaries — the brief, usually simplified and topic-constrained, dictionary-shaped word-to-definition lists found in some books; dictionary-formatted creative works; dictionary-style texts that appear in marketing, consumer goods, and internet memes that may appropriate, subvert, or parody professional standards. The tropes of structure and content in these works reveal what everyday people notice (and don’t notice) about dictionaries.

Between vernacular and professionalized lexicography

- When did the professionalization of lexicography begin?

- What similarities and differences are there between the work of vernacular lexicographers today and the work of important pre-professional lexicographers such as Nathan Bailey and Samuel Johnson?

Insiders and outsiders in vernacular lexicography

Missionaries have documented the languages of the communities they work with and—though now trained by organizations like SIL (https://www.sil.org/training/lexicography)—missionary lexicography has historically been vernacular. What kind of lexicography arises when an endangered or minority language is documented, from the inside, by its native speakers? How compatible are diverse indigenous linguistic practices with (largely western) lexicographical traditions? Does adherence to present-day lexicographical standards erase essential aspects of such languages?

Inquiries and expressions of interest are strongly encouraged ASAP to special issue editor:

Orion Montoya (orion@mdcclv.com)

Final submission deadline July 8, 2019. Publication date November 2019.

MetroLex April 13, 2018

Ellen Jovin

Last April 13, Ben Zimmer launched a special MetroLex meeting of the Dictionary Society of North America with a fish on the wall behind him. It was not a literal fish, but rather, an entirely non-malodorous one from a book written and illustrated by one of the afternoon’s presenters.

Housed in its now-steady home at Columbia University, this MetroLex had two speakers, each with a book freshly published that very week of interest to Lexicographers and The People Who Love Them. The fish was the work of the first speaker, Jez Burrows, whose Dictionary Stories: Short Fiction and Other Findings emerged straight from the loins of lexicographers. (That’s not actually how he put it.) The second speaker was American lexicologist and linguistics professor Lynne Murphy, whose latest book The Prodigal Tongue: The Love-Hate Relationship Between American and British English had just gone on sale.

Jez Burrows Explains His Dictionary-Fiction Process

Ensuring geographical diversity, Jez is an Englishman residing in the U.S., and Lynne is an American who resides in England. (Ben is an American residing in the U.S., but he seems likely to be good with maps.)

Jez confessed to feeling like a bit of an interloper, because he is neither linguist nor lexicographer. He is instead a professional British multi-tasker, making a living as a designer, illustrator, and writer in San Francisco.

The fuel for Jez’s book was sample sentences from dictionaries. And his collaborators were lexicographers, some of whom were sitting right there in the room as he spoke! There was even evidence: a photograph of Jez up to his chin in dictionaries. Slides showed slang dictionaries, non-slang dictionaries, a flash of Playboy—wait, what?—and other word and sentence sources.

Here’s what Jez did: he took some of the loopiest, most poignant, most idiosyncratic sample sentences from dictionary definitions, allowed himself to change pronouns, tweak some tenses, and add a few minor words, then merged them into riotous narratives and birthed a new genre of dictionary fiction.

Interloper? Heck no. Anyone who fishes about in the innards of dictionaries voluntarily for months on end, turns them into suspenseful stories, and illustrates them, too, deserves special lexicographical status. Thus, to the notion of interloperhood, we at the Dictionary Society of North America offer a gentle balderdash.

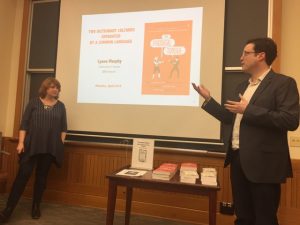

Next came Lynne Murphy, who has been supervising English from the other side of the Atlantic for some time. She writes the popular blog Separated by a Common Language, and her talk, “Two Dictionary Cultures Separated by a Common Language,” tackled a subset of that larger theme.

Ben Zimmer Introduces Lynne Murphy

For attending MetroLexers, she addressed the difficult question of dictionary cultures: how they differ on opposite sides of the Atlantic, and how publishers contribute and participate in those differences.

Lynne described a greater preference in England for unspoken rules and learning by osmosis, compared to an American attraction to “written rules,” “direct teaching,” and “self-help.” The dictionary in the United States acts as a self-help tool in a way that is not universal, or at least not very English.

Behind that self-help tool have often been signs of world-famous American salesmanship. According to Lynne, while English taglines have tilted more towards enticing the word lover, American taglines have offered “the words you need today,” “expert guidance on correct usage,” and “the clearest advice on avoiding offensive language.”

Contrary to the popular impression of many Americans that the British tend to be bossy about how we use English stateside, Lynne commented that a culture of greater linguistic prescriptiveness may be changing language faster here than in England.

Throughout the event, Wendi Nichols of Cambridge University Press and Rebecca Shapiro kindly kept attendees refreshed with food and drink, while stacks of books rested seductively on a table at the front of the room. After the presentations, books were signed, adopted, and taken home to new lives with bibliophiles.

04-13-18 Raucous MetroLex Audience

Yvonne M. Lacy, the daughter of Walter D. Glanze, one of the founding members of the Dictionary Society of North America, has informed us that he died Wednesday, May 30, 2018 in New York City at the age of 89. If you wish to send condolences, she can be reached at ym.lacy.mls@gmail.com. The obituary for Walter Glanze can be found here: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?page=lifestory&pid=189262915