MADELINE KRIPKE 1943-2020

Madeline Kripke, who died aged 76 on April 25, 2020, yet another of New York’s many victims of Covid-19, was for the bulk of her life the world’s leading, if not unique collector of lexicographical material, both historical and contemporary. This was especially the case as regarded her unrivalled library of slang dictionaries and allied ‘counter-linguistic’ material, which had set her career in motion more than forty years ago. The classic poacher-turned-gamekeeper, she moved from a fascination with dictionaries, first encountered as source of delight when very young, to establishing herself as a dealer in their finest or most recondite examples, with a focus on the less respected, but by extension less easily available slang lexis, and finally, falling in love with her stock as must be a temptation for every variety of dealer, to become a collector pure and simple. If one might rewrite the alleged ‘whore’s excuse’, in collecting terms, ‘first she did it for herself, and then she did it for money and finally then she did it for her friends.’ ‘Friends’ being a wide category: her generosity to slang lexicographers was legendary, as it was to all scholarly enquirers. Those who could make the trip were invited to her apartment, others might be given scans of precious material.

Her death brought many personal tributes, plus a lengthy obituary in the New York Times, with variations in the serious press of France, Italy, India and elsewhere. All praised her devotion and the success it brought. It quoted some of her interviews, which talked of ‘the gifted in pursuit of the valued’ and named her ‘The Dame of Dictionaries’.

____________________

I would like, if I may, to intersperse a few personal memories. I am sure that others will have their own, very likely better informed, but these are mine. Living in London I could never be a regular or intimate visitor, but when through some kindly recommendation, perhaps in the Nineties, I was given her address in Perry Street, Greenwich Village, New York city, I was keen to use it. Thus I did, presenting myself.as a slang lexicographer who had just disposed of a collection of P.G. Wodehouse with the aim of obtaining some of the stand-out examples of my craft. I had found a dealer in such dictionaries nearer home, and was starting to pick up her less expensive offerings, when I was told – why do I sense that there was a degree of bated breath and awe involved? – of this woman in New York. If I wanted to play the game, then hers was the team one had to join. So I wrote, and asked for a catalogue. No reply ever came back. Her dealing days, I would find out, had passed. She had succumbed, it would appear, to the bugbear that must bedevil every dealer – whether in books, carpets, furniture, whatever antiquarian speciality one chose – the reluctance to let go one’s stock. Now she had the one job: collecting. She would do it as well as any, and for our discipline of lexicography in general and slang in particular, far, far away better than that.

Madeline Kripke, known as Linnie to her immediate family, notably her brother the world-renowned philosopher Saul, but simply Madeline to the many who revered her, was the greatest collector of dictionaries, primarily those of slang, that the world has known, and very likely will ever know. There was also a sidebar in erotica, notably a collection, again unrivalled, of what were known as eight-pagers, Tillie and Mac or jo-jo books, bluesies and gray-backs, but mainly as Tijuana Bibles. Small, ill-drawn, crude in every sense, vastly obscene renditions of celebrities, mainly Hollywood (both human and animated), in the copulations of someone’s one-handed dreams. Lavatory walls, effectively, brought to print. If such a thing might be envisaged, one of slang’s even naughtier little offspring. She also gathered in material that stemmed from mainstream dictionary-making, notably some unique papers regarding G.C. Merriam at a time when the company had recently acquired the work of Noah Webster.

At her death there were at the very least 20,000 volumes: that was the official figure for interviews and now obits, but the truth was that who – Madeline included – had ever fully counted and it may be that the true figure was double that one; cataloguing, a task that demanded decades, was still in progress. (She was certainly at it in the early 2000s when I visited Perry Street and there was no sense that the job was anywhere near approaching completion). They were shelved, often two-deep, on every wall of her apartment and piled on every once-vacant square foot of floor. Plus tables, chairs, surfaces that might once have been work-tops, the steps of library ladders and even on her bed. It became ever harder to navigate the labyrinthine spaces between them. Madeline would use a torch to investigate the further, darker corners and higher shelves. To make an accurate list would take almost as long as the collecting itself. In addition there were several out-stores. Three was the stated figure, but it seems that there were an extra couple. These last were as yet empty: a state that would not, surely, have lasted.

In 2008 the language expert Ammon Shea, writing in Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages, stated that ‘As far as I am aware, my friend Madeline is the only person in the world who ever made her living solely from buying and selling dictionaries.’ Not, as I have found, wholly true, but certainly no-one had ever collected such works on the Kripke scale. One had to start looking at the great bibliophiles of history, and even those for whom –philia – love – had turned to –mania – obsession – to see those who gathered their beloved volumes to the same extent. This is not to impugn her with the slightest instability: as lexicographers will appreciate from their own world, to be done properly certain jobs demand a degree of obsession, but always, as the popular modifier might add, in a good way. This level of collection was surely one of them. And Madeline was still unique: there may have been other dictionary dealers, but there were no other dictionary collectors remotely on her level, and definitely, unarguably none who specialized in slang.

In the end, I did meet Madeline. In Durham, North Carolina in 2003 where that year’s bi-annual conference of the Dictionary Society of North America was being held. As I was to discover she was a regular attendee at this and other ‘words’ conferences. Indeed, our last meeting came at Julie Coleman’s Conference on Global English Slang in 2013. Madeline would usually turn up with some newly purchased rarity, which would be plucked from a bag and unwrapped to an audience of fascinated lexicographers. I forget what that year’s treat might have been, only that we duly ooh-ed and aah-ed and I at least wished I had both the investigatory skills and the deep enough pockets to have had it for my own. We were introduced. She said yes, she had such books as I had produced (still relatively neophyte productions), but no, she was no longer dealing. Nonetheless I should visit her in New York. She offered a pair of business cards: on one I read the Perry Street address I’d already obtained. Then, ‘Look at the other’, she said, obviously holding back her amusement. ‘This is what I do.’ I looked. It carried a single word, centred and boldface: ‘lexicunt’.

Slang

Slang is to standard language as…let’s think of a city’s inevitably tiny boho enclave set aside from the larger city itself, with its uptown, downtown, rich streets, poor ones, burbs and the rest. Categorise it in dictionary form and the discrepancy is much the same. Socially, linguistically, lexicographically minimus, to offer a little old-school aggrandisement, inter pares. I have written a history of the subset and I could probably list my predecessors, the primary slang lexicographers of half a millennium without vast trouble. A conference of slang dictionary people – Madeline was of course present, she loved such get-togethers – was held at Leicester University in 2013. Were there a dozen of us? Possibly. Twenty? No way, even if Aaron Peckham, creator of the Urban Dictionary, had come to see what the oldies were up to. And if she had restricted her collection to those same thick, square dictionaries, then of course it could never have attained such magnificence. But like a bibliomane who sets out to collect every item of, say, Dickensiana – not just every manuscript and every published edition, even every translation, but every letter, every scribbled note, right down to every piece of household furniture and kitchenware – this was a slang collection that infinitely transcended the peaks. It seems that nothing relevant was disqualified. A vast mountain of matters pertaining to the counter-language, spreading down to the foothills and even beneath. A glorious, one-of-a-kind gallimaufry, an olla podrida of words and phrases. And as is the case in any collection of this scale, the whole edifice vastly greater than a mere sum of the individual bricks.

Why?

In the regular interviews, triggered when some new visitor with a bit of media pull and an editor to impress would visit Perry Street and discover the treasure that it contained and thereafter write about it, there was much marvelling but – perhaps such a query might have been considered naïve, even impolite – seemingly no asking of the underlying question: why? There was some degree of ‘how,’ and much ‘when,’ and of course ‘what’ (there was a list of favourites to be trotted out but for Madeline everything represented, as she put it, ‘a sparkling jewel’) but the question that surely occurred to many readers of the resulting pieces was more fundamental: why does one dedicate one’s life to amassing 20,000 items of which the bulk were devoted to the lexicography of that much-maligned and distinctly marginal subset of dictionary-making: slang?

Why slang? The great collectors, great as in usually (until the 20th century, invariably) male, as in focused on ‘great’ books often written by (more) ‘greats’ (again usually male). Collection is traditionally seen as a male preoccupation. Beermats, football programmes, crumbling boys’ comics, even the serial killer’s gruesome trophies…and while I sometimes blush at the admission, the components – headwords, definitions, etymologies and citations – that go to make up dictionaries of slang. Again we find Madeline to be an exception. Indeed, the mere association of women and slang, not simply as its subjects but as its users and creators, was for so long considered unacceptable, a badge of ‘fastness’, lubricity and a general and reprehensible lack of ‘womanly’ modesty. Not to mention slang’s own take on the female: a man-made language if ever there was one (though who, of course, can actually gender linguistic coinage) with its grim litany of philosophies, simultaneously mixing paedophile omnivorousness – ‘if she’s old enough to bleed, she’s old enough to butcher’ – with probably unmerited critique ‘I wouldn’t touch her with yours’. Ten thousand words for girls and women: every type available except the positive and never a word for ‘love’.

It is perhaps logical – logical in the sense that she stood so much against the collecting grain – that Madeline’s own fascination for slang was launched not merely by the words themselves, though of course she delighted in them too, but also from pictures. The volume in question was a dictionary written by the great 18th century figure, Francis Grose, a militia captain-turned-antiquary-turned-lexicographer of ‘the vulgar tongue’. Grose, an acquaintance of Samuel Johnson, and one whose own peregrinations in Scotland – so much more positive than those of the great Doctor – earned him a celebratory poem from Robert Burns (no mean slangster himself). His dictionary – the Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (a consciously upmarket name for a distinctly downmarket vocabulary) – appeared in 1785 (plus revisions in 1788 and 1796, and a reworking by the era’s star sporting journalist Pierce Egan in 1823). One may consider him slang’s Dr Johnson.

What Madeline stumbled across, browsing a New York bookshop during her lunch hour from the publishers where she worked, was an edition of Grose that had been carefully interleaved with a variety of cut and pasted pictures, used to illustrate at least a selection of Grose’s nominatively determined lexis. It had, as she noted, ‘a wealth of visual material (including newspaper clippings!) showing the contemporary culture in full bloom.’ The embellishments arrived towards the end of the Victorian era; the author remains a mystery. She paid $100 and probably thought it plenty. It was worth every penny.

The Grose was of course something of a rarity, an amateur devotee’s labour of love. Dictionaries were sometimes illustrated, but in a wholly utilitarian manner – here’s a plough, there’s a magpie – and pictures never accompanied any of the slang variety. (Other than occasionally in the ‘beggar books’ of the 16th century when readers of such ‘shock, horror’ pamphlets were regaled, for instance, by woodcuts of some hapless whore or villain being whipped at the cart’s tail). One might suggest that slang’s particular obsessions – loosely shorthanded as ‘sex and drugs and rock and roll’, with the widest possible interpretation of the latter – should be a natural for visual add-ons. Perhaps, but slang, being more a collection of synonyms than a full-on language, is nothing if not repetitive. Fourteen hundred words for penis, the same for vagina, eighteen hundred for heterosexual intercourse: even the most dedicated fan of YouPorn and its infinity of clones might falter before that many money shots.

So, stand up book one. And 40-plus years and at least 20,000 successors later…

It is likely that the collection surpassed even those of major academic and museum libraries. It had, for instance, the author’s own copy of Lexical Evidence from Folk Epigraphy in Western North America: A Glossarial Study of the Low Element in the English Vocabulary (1935), Allen Walker Read’s deliberately heavyweight title for an alphabetical study of the ‘bad’ words found in graffiti on the walls of men’s rooms in national parks. Slang has always battled the censor, even when its compilers had impeccable credentials.

Other stand-out titles dealt with Websteriana, cowboy lingo, books that struck Kripke as ‘odd in some fashion’, the slangs of various European languages, and so much else. Like the Read volume, many were what the trade calls ‘association copies’, i.e. in some way linked to their author, with a signature, a message to the recipient, manuscript amendments and the like. Collectors are invariably drawn to such refining specifics. But the truth remains: to choose from such a multitude is almost pointless. Not until the collection is fully catalogued, until each and every piece of paper – bound or otherwise – is identified and attributed, will we know everything of what she achieved.

Money

The traditional bibliophile, and perhaps even more so bibliomaniac, depended on one vital input: a seemingly inexhaustible fund of cash. Aside, that is, from those who simply robbed pre-existing libraries or bookshops, and even, in what appears to be a single case, murdered half a dozen rivals so as to get their priceless incunabula, from Latin meaning ‘swaddling clothes’ or ‘cradle,’ the specialist term for works that were printed in the very first dawning of moveable type, from c.1450 to 1500. There were, it is estimated, around 50,000 such books printed; 20,000 are lost and the remainder rarely hear the auctioneer’s hammer.

For a while, the former robber barons, now remade as the fabulously rich philanthropists of America’s late 19th century ‘gilded age’, saw books as a form of competitive willy-waving. My elephant folio’s bigger than yours. Like real-life Charles Foster Kanes men – as ever it was almost always men – like J. Pierpoint Morgan plundered the world – often bear-led by dealers who benefited vastly from their judicious dangling of literary treasures before clients for whom price was truly no object – to build mouth-watering collections and either incarcerated them within purpose-built libraries or handed them over, suitably name-checked above the marble-clad entrance, to the institute of their choice.

Even such a rarified figure as H.S. Ashbee, a wealthy merchant who as the coarsely punning ‘Pisanus Fraxi’ was the 19th century’s leading British collector of what the book trade called ‘curiosae’ and the great unwashed termed ‘porn’, willed his books to his nation’s grandest repository: the British Museum, where, though timorously gelded of many titles, they became the founding members of the ‘Private Case’. (The Museum, it should be added, was forced to take the smut as a condition of laying hands on what they really wanted: Ashbee’s superb collection of Cervantes, he of Don Quixote fame; they have presumably felt it was worth the risk: the last time a first edition of that classic came up, in 1989, the hammer descended at $1.5m)

Slang, of course offers no incunabula (or none we know), though examples of the language of criminal beggars, extracted from the records of court cases, appeared in the late 15th century. Nor was Madeline a robber baroness, nor, at least in a sense that might be understood by a Bezos or a Gates, a philanthropist. There was, however, some money around. And an influential friend who knew better than most what to do with it. Her parents, Rabbi Myer and his wife Dorothy, lived in Omaha, Nebraska. As reported in the rabbi’s N.Y. Times obituary of 2011:

‘When they were younger men, Rabbi Myer Kripke and Warren E. Buffett belonged to the same Rotary Club and lived a few blocks from each other in the Happy Hollow neighborhood of Omaha. They played bridge together with their wives. The Buffetts would invite the Kripkes over for Thanksgiving.

By the mid-1960s, Rabbi Kripke and his wife, Dorothy, an author of children’s books, had inherited some money and saved a little of their own. The total came to about $67,000. The young Mr. Buffett was building a local reputation as a shrewd money manager, and Dorothy Kripke offered her husband what now seems glaringly obvious advice: “Myer, invest the money with your friend Warren.’

The rabbi, feeling that his nest-egg would not impress the future billionaire, held back. Eventually he took the plunge. In time the $67,000 was transmuted into around $25 million.

To what extent Madeline benefited is perhaps to be investigated. She came to New York where her mother saw her college, Barnard, as sited usefully near the Jewish Theological Seminary, a possible source of a ‘suitable’ husband. The ‘nice Jewish girl’ had left the mid-West in more ways than geographical. The counter-culture was taking off, and reborn as ‘something between a beatnik and a hippie’ she leapt aboard.

She followed Barnard with Columbia (a graduate course in Anglo-Saxon) then worked as a welfare case worker, teacher and even considered the still new world of computers. None lasted and she began editing for a publisher (she worked as a freelance copyeditor long afterwards). and then, as the slang collection took its grip – ‘I realized that dictionaries were each infinitely explorable…they opened me to new possibilities in a mix of serendipity, discovery and revelation’ – as a book dealer. Presumably an income came in, presumably books were sold to purchase others. But the dealing faded away with the last century, while the collection moved ever on. Her last purchase, un-named but noted, was due to cost $60,000. Pocket change in world where Leonardo’s Codex Leicester has been auctioned – to Bill Gates – for $30.8m, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales for $7.5m and a Gutenberg Bible for $4.9m, but this is slang and that kind of price remains less than quotidian. By such standards her league may to many have been minor, but Madeline was its MVP.

Where?

Collections, their first life brought to an inevitably untimely end by their creators’ death, have an afterlife. Unless, surely against their owner’s wishes, they are broken up and sold off piecemeal, the big question is always: what happens now? where do they go? This too is a story that, at least at time of writing, has yet to unravel.

‘If I magically had my druthers,’ Madeline told one interviewer, ‘I could just buy a building and declare it the Dictionary Library or the Lexicography Museum, and have an institution carry it on.’ The problem is that druthers were not on offer. Covid-19, ill-mannered, voracious, insatiable, offers its victims no time.

Madeline died intestate – there was no will nor were there instructions as to the fate of the collection. There were many plans for the disposition of the collection: my partner, sworn to absolute secrecy, which she never betrayed (and after Madeline’s death admitted that after fifteen years she had forgotten exactly which new home had been specified), was one of what turns out to be several intimates who had been vouchsafed the supposedly final destination. That this should and would be an institution, presumably a college or similar, seemed in no doubt, but which one precisely? Did Madeline intend to offer the collection as a gift? or would there be a price? No-one knew. In the aftermath of her death and as the news spread, a number of self-appointed claimants contacted the family. Mainly colleges (who made it clear that much depended on the collection being gifted), but one an anonymous individual who announced himself as acting for a seriously wealthy man who wanted to give the collection to the institution of his choice but would not reveal himself until the deal was done. Dealers, of course, were in hot pursuit, but that would almost inevitably mean that the collection would be cherrypicked for what the trade calls ‘hot spots’ – and there are many such – and the rest, the vast representation of slang material that by the very nature of its subject matter would, when assessed in single sheets or pamphlets, be declared ‘worthless’.

But as I write none of this can even be considered. Dying intestate and with the collection left in seeming limbo has kicked over the inevitable can of worms. Where there’s a will, as the cliché has it, there’s a lawsuit. And where there isn’t one… Then, of course, there is the taxman, the IRS, who will want their lucrative pound of flesh. Without a will or statement of a gift, it seems, that mulct cannot be sidestepped. Slang, so value-free in the wild, turns very desirable in captivity. How these tens of thousands of items will be valued presents a problem all of its own both as regards the sheer volume of material to be assessed, and the fact that while the taxman dictates the valuer of choice, who but a small group of slang experts, actually know, or can at least offer an informed guess, what the prices might be. The best, perhaps the one true authority, of course, would have been Madeline herself.

What happens next is unpredictable. There are, when death joins the party, no happy endings. Slang devotees must hope that this is a rule-breaking exception.

Madeline died, wholly unexpectedly, of Covid-19. She was expected to recover. She did not. Given the restraints of social distancing, and the simple fact of her country- even worldwide circle, it was fitting that her memorial was held via Zoom. As well as her brother Saul Kripke, and his colleague Romina Padro, those on-screen were the slang lexicographers Michael Adams, Tom Dalzell, Jonathon Green, Jesse Sheidlower and Terry Victor; John Morse (former President and Publisher of Merriam-Webster); Peter Sokolowski (Senior Editor and Lexicographer at Merriam Webster; Richard Newsome (a longtime collaborator with Madeline on cataloguing her books); Bruce McKinley (of the Rare Book Hub website) and Ammon Shea (OED lexicographer and author of Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages).

As Tom Dalzell, offering a summary to those who attended, put it, ‘You could see the admiration and affection that we all felt for her.’ The sometimes clichéd promise that ‘she will be sorely missed’ was at least on this occasion wholly true. It is to be hoped that a longer-term memorial will be provided by the establishment of her collection in the library that she always desired.

___________________

Writing of his own work, which took hard-boiled detective fiction, usually restricted to the pulp magazines, and rendered it something of an art form and credited as such, Raymond Chandler offered this line on his own work: ‘To accept a mediocre form and make something like literature out of it is in itself rather an accomplishment.’ In the hierarchy of language, slang is that ‘mediocre form’ and in treating it like literature, Madeline Kripke took it to a higher plane.

–Jonathon Green

Madeline Kripke collected, curated, and shared. When friends visited her apartment, they realized, at some point, that she had set aside an unexpected item of personal interest to them. She could privately savor the surprise for hours, and then, the reveal! Unlike Madeline and many slang lexicographers — Dalzell, Green, Sheidlower, Thorne, for instance — I’m a country person, neither urban nor urbane. Thus, because I was rarely in New York City, we corresponded. Occasionally, she would send me photographs of other photographs or plates from books, portraits of lexicographers or illustrations of the material presence of dictionaries or nearly absurd popular representations of heroic lexicographers.

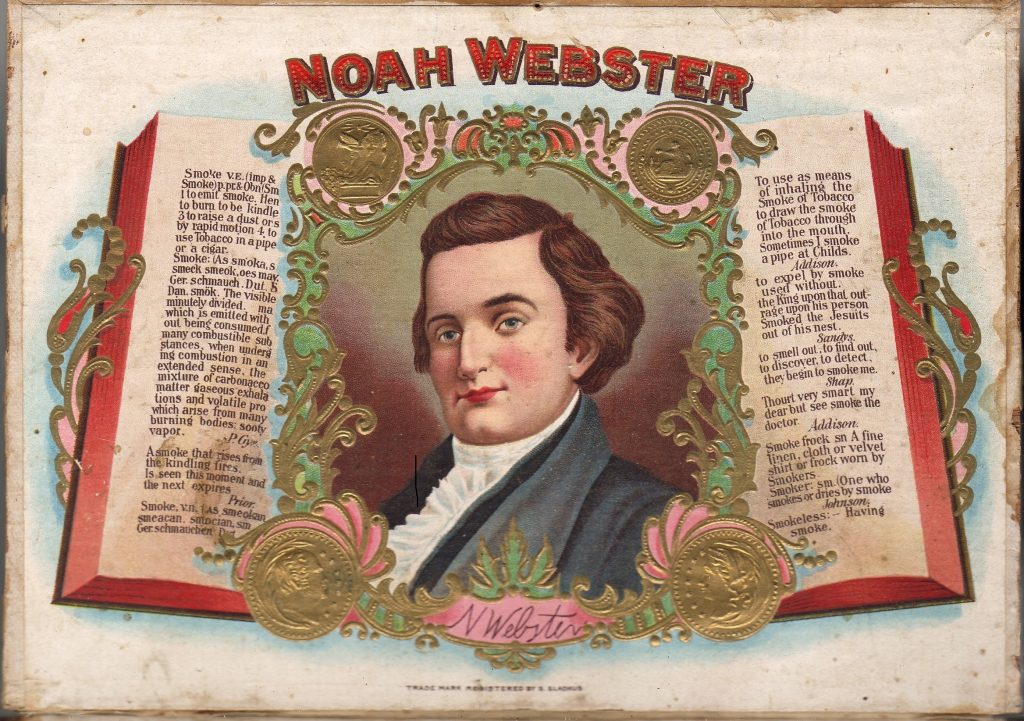

For instance, in this last category, I have in my files an image of the inside of a Noah Webster matchbook, another of a Noah Webster cigarette card. Athletes and sportsmen, actresses and war heroes, race horses and airplanes — those were the typical subjects of such cards, but in the panoply of human activity represented by them, lexicography had its place, and the trick was to find a lexicographer so famous that he fit the medium. Out of the blue one day, I received a brief e-mail with .jpeg attached. It opened to an image of the inside cover of a cigar box. I can’t read the name of the maker in the image, it’s a bit blurry on the bottom edge, but someone had actually trademarked a brand of Noah Webster cigars. The cover is garishly red and gold, with a picture of Noah Webster in the middle, framed in medallions and filigree, set against the background of a dictionary open to the definition of the verb smoke and various quotations from famous authors illustrating that word. Usually, Webster looks dour, pale, mildly disheveled. This image gives him lustrous brown hair, full cherry lips, and rosy cheeks — a romantic Webster. The accompanying e-mail said simply, “Michael: Ain’t this a honey! Madeline.”

Some pictures she sent were quite conventional, engraved plates of famous dictionary makers: Henry Alford, Jospeh Baretti, Jacob Grimm, John Jamieson, Lindley Murray, Max Müller, for instance. And some were slightly more interesting photographs, say, of Trench, Worcester, Wright, Bradley, Craigie, and Murray (no Onions). My favorites are of David Guralnik at his desk, smiling, hands behind his head, arms akimbo, shot from above. Then, there’s a suite of Emile Littré, in each with arms defiantly crossed, his scowl savage — no honey there.

Sometimes, you could tell she was showing off a bit, as when she sent an image of a charcoal drawing of H. L. Mencken by Richard Hood, signed by both. I don’t have anything like it, but if I did, I’d figure out how to show it off, too. One reason for my being, I’ve realized since she died, was to serve as an audience for Madeline’s collection, someone who appreciated the uniqueness of the items in it, but also the profound, learned, fascinated curation behind it, as well as the expressiveness of the objects themselves. I wasn’t alone in that audience, of course, and I wasn’t even in the front row, but I’m lucky to have been part of it. With my memories and the .jpegs to prompt them, I’m still part of it and, I suppose, will be until I die, too.

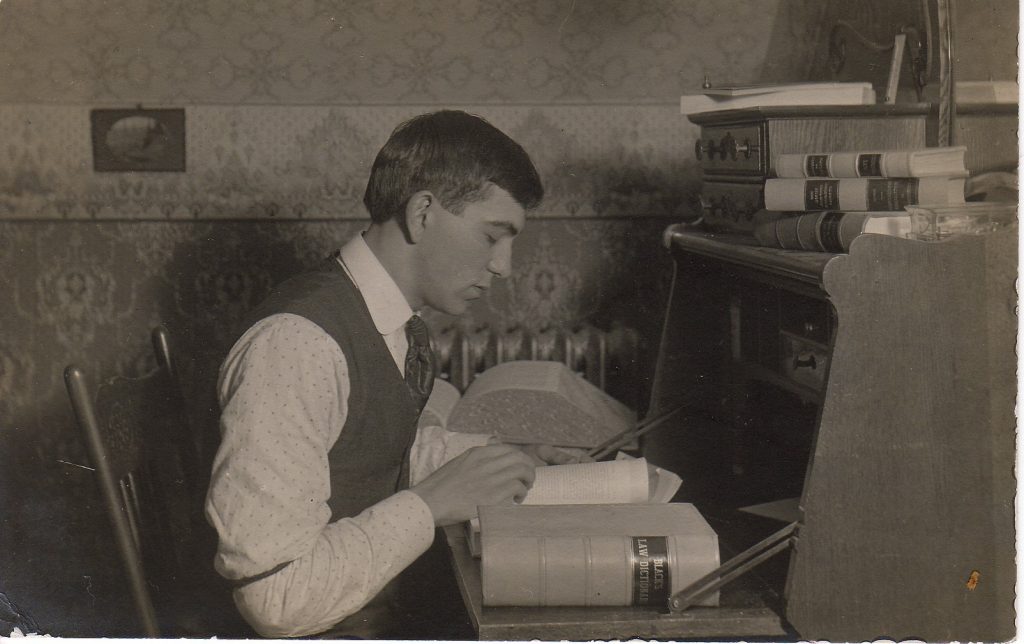

From our conversations at DSNA meetings, Madeline knew what to share with me, what would inform and delight me. That’s why she sent me a photograph of the entire I. K. Funk and Company on the sidewalk in front of their building. Isaac Funk didn’t make those dictionaries on his own, and Madeline shared, not only the photograph, but my sympathy with those whose names don’t appear on title pages. Similarly, a photo she titled “NID Sales Team,” with the sales force — men and women — arranged around lunch tables. I don’t know the dates of either picture, but I’d guess turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century for Funk and Company and roughly 1934 and publication of WNID2 for the Merriam-Webster folks, given their clothes. She knew, too, that I think about dictionaries, not merely as texts, but as cultural objects signifying social class, among other things, so she sent me a telling portrait of a young man studying, with law books open around him, and a very substantial Black’s Law Dictionary on the edge of the desk, closed with its spine ironically confronting the viewer. Not just good stuff, these photos, but the best.

Somehow, Madeline knew I’d study and write about Allen Walker Read before I did. She sent me many photos of him, one the ubiquitous headshot of Allen at about forty-years, another one of him sitting on a sofa, handsomely, perhaps in her apartment, pre-collection, when there’d have been a sofa to sit on. I had forgotten about a picture of Sgt. Read at a desk, probably at 165 Broadway, home of the United States Army Language Section during World War II, until I looked through what Madeline had sent me over the years this spring. My favorite, of which she sent several edited versions, so she knew it would be my favorite, shows Allen thirty feet in the air, hanging by one hand from a windmill in a cornfield, with a smile as big as the sky. Madeline had a wicked sense of humor, but a sense of whimsy, too. When I need to remember what joy looks like, I call up that photo. Madeline gave me that joy.

Michael Adams

Memories of Madeline Kripke

I met Madeline Kripke within the first 10 years of my becoming chair of the special collections department in the library at Indiana State University in 1986—I don’t recall precisely when. She introduced herself as a dictionary collector and bookseller at a DSNA biennial meeting. I recall at the 2009 DSNA meeting in Bloomington, she and I spent time talking of her collection and her plans for it in the future. These included a catalog and a future home for her books. How far along the catalog is, I can’t say. It would be an enormous expense and a time-consuming task to create a catalog of 20,000 or more titles.

The last time I saw Madeline was in Toronto in 2011. Another collector, Jerry Farrell, was in attendance, and we three spent time hobnobbing with one another. Madeline was at ease with others who shared her interests. I wasn’t able to attend another meeting until 2019, so I don’t know if she was able to go to additional meetings. I wasn’t surprised she was absent at the meeting in Blooming in 2019. She had developed health issues that kept her close to home with her books in New York.

Although Madeline was a bookseller, I think this was something she did more from a sense of duty to scholars whom she had befriended than as a livelihood. Although I expressed an interest in getting books from her for the Cordell Collection, which I helmed for about 25 years, she never shared a list with me. In fact, I know of no bookseller catalog offerings or even lists which she issued. Somehow she got to know people, and frequently she would find what they needed in her extensive holdings. It was all done informally.

Madeline’s devotion to the history of lexicography is evidenced by her years of collecting and her support for lexicography research. Her generosity in sharing her knowledge and books with others denotes just how caring she was. Let’s hope her collection, her legacy, remains intact. I know that this is something Madeline wanted.

David Vancil