The big news here is the farewell celebration for DARE. We also have a piece by Eugene Green about use of the Middle English Dictionary. And we commemorate the passing of Herbert Ernest Wiegand.

DARE Farewell Celebration

October 27, 2017

As of the end of 2017, the last three of DARE’s employees are no longer working, and the Dictionary of American Regional English is officially out of business. We decided earlier to end with a celebration, focusing on what we have accomplished: five large volumes covering the whole of the alphabet plus one supplementary volume with geographical and social maps, an index to all the regional and usage terms used (e.g. Danish, euphemism, folk-etymology, Gulf States, Vermont, middle-aged, Shawnee, taboo) followed by all the entries in which such a term occurred, and more – great fun to browse. DARE also has an online presence.

About 150 former DARE staff members, volunteers, student workers, supporters, and friends showed up on Oct. 27 in Madison to help us celebrate. Many still live in Madison, but many others came from afar. Thank you all for coming! It was so great to talk with people we hadn’t seen for years, or even decades, to reminisce and find out what they are doing now. And great to meet others we had never met, ones before our time at DARE, or even some after our time there. But, oh, the time was too short to talk with all of them! Still, a good time was had by all.

Joan Hall has collected the comments of all the speakers at the celebration, including those of Steve Kleinedler, President of DSNA, for your enjoyment.

Luanne von Schneidemesser

We have remarks by Joan Hall, Rebecca Blank, Susan Zaeske, Steve Kleinedler, and Gabriel Sanders.

Joan Hall:

Good afternoon, and welcome. I’m delighted to see so many of you here today, and to realize that some have come from as far away as California, Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York! We are honored that you cared enough to make the trip.

I’m also extremely pleased that many former DARE staff members and student assistants were able to come. And two of DARE’s original Fieldworkers are here! Barbara Myhre Vass did interviews for DARE in California and Illinois, and Peter Lee worked here in Wisconsin. (Please raise your hands.)

One thing that has been very gratifying over the years is that many people from the Madison community as well as the University have loved the project enough to volunteer their time to help us out. There are dozens of people who have done so, but one person in particular has devoted a huge amount of time to DARE, and we feel that she is a member of our staff: Judy Taylor will next week celebrate her 30th anniversary as a DARE volunteer. Judy, we thank you.

If you’ll look around you and check people’s nametags, you’ll see that there are quite a few with names printed in RED: those are people who have worked on the project as staff members, students, or volunteers. They have all been important to our success.

And if you look more closely, you’ll notice that two nametags are printed in BLUE–those represent members of our Board of Visitors, whom you will meet in a few minutes. Feel free to use these color-coded nametags as conversation starters!

We are honored this afternoon to have Chancellor Rebecca Blank here, and she will address us in just a moment. But first, I’d like to say a few words (hold up a sign for each):

bobbasheely

mubble-squibble

ramstugious

upscuddle

scrid

Where will you find these? In DARE, of course! And if you would like to know what they mean, feel free to browse in the two sets of print volumes that we’ve brought today, one on the far wall, and one in the entryway.

People often ask me if I have a favorite word, and I do: it’s bobbasheely. And later during this party I’m going to take this sign and go over to the corner and the photo booth and have my picture taken with it. I encourage all of you to do the same–alone or with a friend or two–choosing your favorite from a great selection of wonderful DARE words. You’ll have a souvenir photo, and DARE will have a copy for our guest book.

I would now like to introduce Chancellor Rebecca Blank. Chancellor Blank is an economist who has worked in three different presidential administrations.

She holds a doctoral degree from MIT, and has served on the faculty at Princeton, Northwestern, and the University of Michigan, where she was dean of the Ford School of Public Policy.

She came to the UW–Madison in 2013.

Please join me in a warm welcome for Chancellor Rebecca Blank.

Chancellor Blank:

Thank you, Joan, for that kind introduction. I am delighted to be here to share in this celebration of an extraordinary work of scholarship spanning 50 years. The Dictionary of American Regional English has given us a whole new way to understand not only language but the rich array of cultures that define this nation.

Let me begin with heartfelt congratulations to:

Joan Houston Hall, chief editor emerita,

George Goebel,the dictionary’s current editor, and

Everyone affiliated with DARE over the years for this exceptional achievement.

(applause)

I want to thank the members of the DARE Board of Visitors who are with us today for dedicating themselves to helping steer this project over many years:

- Cynthia Moore

- Erin McKean

It is remarkable to think that it’s been more than half a century since students armed with tape recorders fanned out across the country to start collecting words and phrases for DARE. From those humble beginnings grew what Time called a work of “staggering scholarship.”

Today, DARE is heralded around the world as a monumental accomplishment — what Harper’s called “one of the most poignant reference books ever compiled.”

It has, of course, become essential to linguists, librarians, and researchers. But it has also proven invaluable to police investigators trying to trace ransom notes … intellectual property lawyers … and Broadway dialect coaches.

DARE reflects the very best of humanities scholarship and the Wisconsin Idea. Your work has helped Wisconsin and the entire nation to understand, share, and celebrate our history and culture.

Over the summer, my husband Hanns and I spent a long weekend driving along the Great River Road on Wisconsin’s western border. In a blog post, I mentioned that we were still debating the proper pronunciation of the word used to describe marshy areas along the Mississippi. Joan immediately responded, explaining that most people say “sloo,” although a few say “sa-loo” or “sloff.” And if you’re from the Northeast or Central Atlantic areas, you probably avoid the whole issue and say backwater or lagoon.

It is just a lot of fun to learn that there are at least 20 different ways to refer to the strip of grass between a sidewalk and a street, and that, if you’re in need of an outhouse, it’s a “biffy” in Wisconsin, a “garden house” in Pennsylvania, and a “johnny house” in Georgia.

For those of us who love language, DARE is a joy. But it’s also serious scholarship, and I want to make three important points about that.

First, DARE is an exceptional example of a public-private partnership. It has been supported with millions of dollars in state, federal, and private grants. That’s not uncommon in the sciences, but it’s quite unusual in the humanities.

Second, over its long history, DARE has employed and trained hundreds of graduate and undergraduate students from a variety of majors, enriching their education and, for many, shaping their future careers.

Third, the national and international acclaim DARE has received over the decades has reflected on this entire university, burnishing our reputation for excellence in the humanities. We thank you for that as well.

While tonight marks a milestone and a change for DARE, we all know that this is far from the final chapter. DARE’s impact and influence will continue unabated for generations and centuries to come.

Congratulations, and thank you for inviting me to mark this very special occasion with you!

Joan Hall:

Thank you, Chancellor Blank. We certainly appreciate your warm words for us personally and for this long-term project.

As part of the Department of English for our whole history, we have been graciously housed and warmly welcomed by our colleagues there. We have also received generous support and advice from the Graduate School and the College of Letters and Science. Here with us today is Associate Dean of the College of L&S, Susan Zaeske, who will also share a few remarks.

Dean Zaeske:

Boy oh beans!! Hoo-wee! Hot Ziggety! Holy Mackerel! And hip-hip-hooray for generating a half century of exemplary research that has contributed significantly to our understanding of American language and culture. Since the origins of this tremendous project in the 1940s when English professor Fred Cassidy conducted a pilot dialect survey in Wisconsin, the College of Letters & Science has been honored to serve as the home of what by 1962 became the Dictionary of American Regional English.

Speaking for the College of Letters & Science and Dean Karl Scholz who is unable to be here this afternoon, I want to echo Chancellor Blank’s words of gratitude for everyone who has worked on DARE and joined Letters & Science, the Mellon Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities among other funders in supporting DARE over the decades. Thanks to current editor Goebel and to members of the DARE Board of Visitors for their advocacy and guidance.

And I want to offer special thanks to Joan Hall. I will read from a February 2012 letter that former L&S Dean Gary Sandefur sent to Joan upon completion of the last volume of DARE. He wrote, “I also want to thank you personally for your leadership since you joined the DARE staff in 1975. You have played a significant role in carrying out the DARE mission through your dedication to Fred Cassidy’s vision, your advocacy and education on the revelations of DARE’s resources, and your guidance of the project following Fred Cassidy’s passing. In all of these activities you have come to exemplify academic staff leadership and excellence in the College of Letters & Science and at the UW-Madison.”

The chancellor mentioned how DARE has contributed to crime solving, intellectual property law, and the excellence of Broadway performances. I would like to stress how it has brought prestige to humanities research and particularly the humanities at UW-Madison. When I attend meetings of national humanities organizations such as the American Council of Learned Societies or the National Humanities Alliance and introduce myself as a humanities dean at UW-Madison, often the reply is, “Oh, you work at the DARE school.” Yes, I do.

Today we celebrate the creativity, diligence, and scholarly attention that has been invested into DARE for over half a century. The breadth of the collection and attention to archival and linguistic detail embodied in DARE have provided a rich and lasting cultural resource that will serve generations to come. Congratulations on this monumental achievement.

Joan Hall:

Thank you, Susan.

In addition to being a part of the University community, DARE has also been active in two scholarly societies, the American Dialect Society (which is our titular sponsor), and the Dictionary Society of North America, where we can interact with others from around the world who share our rather unusual occupation. I’m delighted that the current president of the Dictionary Society of North America is here today, and Steve Kleinedler would like to greet you on behalf of the society.

Steve Kleinedler:

The dismantling of a dictionary is a somber event. In my 28 years as a lexicographer, I’ve seen it happen far too frequently. Whether done incrementally by periodically slashing editorial and production positions or suddenly by announcing an unexpected closure, the industry has been drastically contracting. Unlike our colleagues overseas, not even the backing of educational institutions is enough to sustain dictionary projects in the modern American business and political climate.

As the president of the Dictionary Society of North America, an organization whose history is deeply intertwined with the Dictionary of American Regional English, it is my sad duty to witness the end of another American lexicographical institution. While we celebrate the work of countless scholars, lexicographers, designers, production personnel, volunteers, not to mention the contributions of so many speakers across the country going back to the 1960s, we do so with the bittersweet realization that it is coming to a close.

If general purpose dictionaries document the way a population uses language, regional dictionaries document the different ways a population uses language.

To see one’s own lexicon, one’s own way of speaking, one’s idiolect cataloged, described, and documented is extremely powerful and vital. In the late 90’s when I was working on page proofs for the fourth edition of the American Heritage Dictionary, I was shocked to see boughten was marked as a regional word. Boughten is a core vocabulary word for me, not just in phrases like boughten bread (which I heard frequently growing up in contrast to the default kind of bread – that which was homemade), but as the past participle: I’ve boughten some cupcakes for desert. So I turned to the Dictionary of American Regional English, and read all of the examples and looked at the distribution patterns. I felt validated — even though no one else on staff (and at that time, we still had a big staff) used it and everyone thought that it “sounded funny.” I was validated. I have learned how to use lie and lay and sit and set and whom, but I don’t budge on boughten. It’s an entrenched part of my idiolect, enshrining my upbringing in Michigan.

Lexicographers at DARE conducted research on a national level to document regional variation, validating speakers who might otherwise have thought their regional dialect was stigmatized, long before self-selected populations could take internet quizzes, selecting whether they watch fireflies or lightning bugs in the nighttime sky.

Like all the other American dictionaries that have been unceremoniously gutted in the past two decades, the mantra of “content wants to be free” continues its unblinking algorithmic march. Although everyone here has benefited from instantaneous electronic lexicographical resources, there is one thing people can do that data trawling cannot, and that is account for context. This fact will likely remain so until the Singularity. Algorithms lack context. Some may argue this is a feature, but it is a bug.

The Dictionary of American Regional English oozed humanity: the humanness of the lexicon that it describes, and the humanness of the people who compiled it. Joan, Luanne, and many others including the late Frederic Cassidy have spent their entire adult lives on this noble endeavor. It is with great sadness we are here to witness its end, but it is important that we celebrate their immense achievement. It is through their work that the concept of regional variation is something to be upheld instead of dismissed; that diversity of language is an important component of our culture that should be documented. The six volumes and subsequent quarterly updates are a legacy to English spoken in the United States; their importance cannot be overstated. Today, we honor this legacy.

Joan Hall:

And now I’d like to introduce you to my longtime colleague, George Goebel, who has been with the DARE project since 1983, and who succeeded me as Chief Editor.

[Joan Hall summarizes his talk:

He welcomed people and drew a name out of a bag for the winner of a Wisconsin Historical Society mug with an image of a “bubbler.” He then mentioned that we had two stations where people could explore the digital version of DARE, and three stations where they could listen to any of the audio recordings we had recently made publicly available.]

Now please enjoy the refreshments, the displays, the audio recordings, the digital DARE, and the pop/soda/soda pop map over in the corner. Thank you for coming!

Link to audio recordings:

https://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/collections/amerlangs/

Link to press release:

https://news.wisc.edu/american-voices-from-the-past-live-again-as-dare-recordings-available-online/

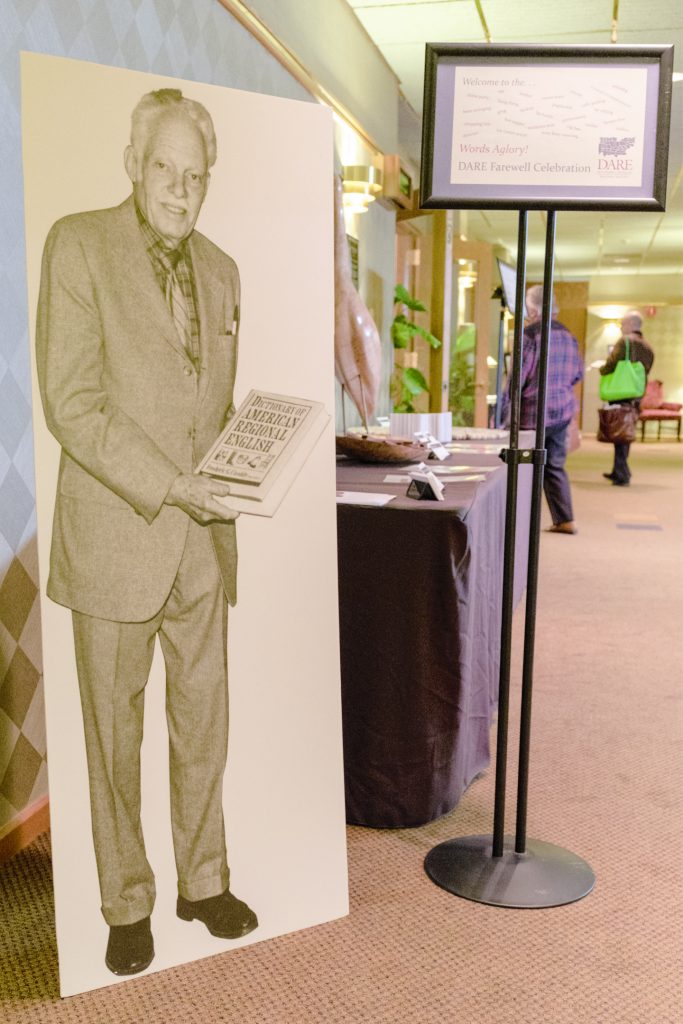

1: “The spirit of Fred Cassidy is with us”: When we celebrated the 100th anniversary of Fred’s birth in 2007, we had this photo blown up to almost life-size, and he has come to all of our parties since then.

2: “Pre-remarks”: People enjoyed the refreshments before we had our “program.” Left front is Kevin Kurdylo, Librarian and Archivist who was instrumental in our digitizing all the DARE audio recordings; shorter woman in pink at left: Sarah Thomas, a former student worker; woman with red and black scarf, Anja Wanner, a linguist in the UW English Department; woman in pink in center: Judy Taylor, our faithful volunteer for 30 years; right front, Marty Nystrand, Professor of English Emeritus; far right, Denise Lamb, former graduate assistant.

3: Susan Zaeske, Associate Dean for Humanities, College of Letters and Science.

4: Denise Lamb, former graduate assistant, with the two words she chose to be photographed with in our photo booth.

5: L to R: Denise Lamb, former graduate assistant; Mary Jo Heck, former graduate assistant; and Rosemary Dorney, friend of DARE, selecting DARE words to be photographed with.

6: L to R: Mike Sweet, friend of DARE; Ted Hill, former DARE Editor; Roland Berns, former DARE Editor.

7: Joan Hall with her favorite word.

8: L to R: Phillip Certain, former Dean of the College of Letters and Science, who ensured DARE’s future when, in 1997, he agreed to support the position of a fund raiser for three years; Joan Hall; Nancy Nystrand, friend of DARE.

9: Joan Hall with Gabriel Sanders, former student assistant (for all but one semester of his four years at the UW-Madison).

10: Poster to explain the art works based on DARE words, which we exhibited at the party.

11: DSNA President Steve Kleinedler.

12: Joan Hall; Rebecca Blank, Chancellor of the UW-Madison; George Goebel, Chief Editor, DARE.

All photos taken by George E. Hall

Eugene Green, Boston University, has been working with the Middle English Dictionary for many years and has this to say about how its resources can be tapped.

The Middle English Dictionary as a Resource for Linguistic Analyses

In its current online form the Dictionary presents beguiling resources, at least for grammarians who value its data but find access to them daunting. If its abundant quotations outmatch any other online source of Middle English, tapping them effectively demands an innovative approach different from methods already familiar. This demand issues from the challenge of conceiving efficient, reliable ways to harness quotations arranged under headwords for studies of grammatical patterns. The possibility of supporting grammatical inferences comprehensively by means of thorough quotation makes a search for an efficient approach to the Dictionary’s lexical resources highly inviting. Paul Schaffner’s announcement (Newsletter Fall 2017) of current plans to modify the Dictionary, to turn it from a static to a dynamic resource opens again a grammarian’s quest for workable approaches. After all, his announcement suggests that the Dictionary as a compendium aims to provide “a node in a network of historical dictionaries, electronic editions, text portals, and other linguistic resources” Yet the possibility that under “linguistic resources” the Dictionary as a dynamic compendium would link together with Middle English parsed texts compels scrutiny. What adjustments, for example, would suitably tie the Dictionary to the Penn Parsed Corpora of Historical English and the newly Parsed Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English? Currently the Dictionary’s terms of usage, such as agent, agency of, auxiliary, passive voice, p. ppl., provide guidance on the deployment of words – bẹ̄n, worthen, of, and thurgh among them. To suppose, however, a wide extension of these terms, in a manner compatible with the parsed texts now available, transforms the Dictionary’s ambitious undertaking into a barely conceivable enterprise.

Nonetheless, the Dictionary as a resource for grammatical analysis works under a set of assumptions on methodology. First, a method that approaches it as a compendium to read closely offers benefits sooner than one viewing it as a resource containing more than 800, 000 quotations. If read closely, the Dictionary’s terms of usage reveal a considered practice designed to order coherently the extensive variety of Middle English forms during more than four centuries. The term auxiliary, found under such verbs as bẹ̄n, worthen, also shulen, introduces a full spate of forms from early to late Middle English. On the other hand, close reading requires grasping a rationale for the absence of auxiliary under the headwords cǒnnen and mouen. A like exercise applies to the occurrence of agent or agency of under only some prepositions.

A second aspect of methodology applies to the design of the analysis under consideration. Generally, the Dictionary is a valuable compendium for well circumscribed study. To suppose that it will readily and adequately supply discriminating quotations in the passive voice soon enough daunts even patient effort. But to limit initially the scope of study to the use of bẹ̄n and worthen as auxiliaries collocated with past participles by Laȝamon and Orm promises worthwhile findings. And such findings are likely to generate further questions, their scope also constrained, that make the Dictionary’s riches economically approachable.

Herbert Ernst Wiegand

08 January 1936 – 03 January 2018

During the last four decades Professor Herbert Ernst Wiegand, who passed away on 3 January 2018, has been one of the most prolific and influential scholars in the field of metalexicography and dictionary research. In the academic world he was respected and appreciated as leading researcher, scientific organiser, dedicated colleague and loyal friend. Herbert Ernst Wiegand was a versatile scholar who published in various fields of the broader domain of linguistics, especially theory of language, lexical semantics and text linguistics, as well as Germanic studies. However, his main contribution has been in the establishment of lexicography as an independent discipline.

In 1972 Wiegand was appointed as professor for theoretical linguistics at the Philipps University of Marburg. This was followed by a period at the University of Düsseldorf before taking up a position at the Ruprecht-Karls University of Heidelberg where he was Professor Ordinarius from 1977 until his retirement in 2004.

His 487 publications, published during the period 1967-2017, include his magnum opus Wörterbuchforschung (1998), and numerous articles focusing on a wide variety of topics from the field of lexicography. The dominant focus in this extensive publication list (approximately 20 000 printed pages) is on dictionary structures. He identified, analysed and discussed a comprehensive selection of dictionary structures in minute details. With this contribution he elevated the lexicographic discussion and established it as an acknowledged scientific domain. In his four-volume Internationale Bibliographie zur germanistischen Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung he provided the most significant bibliography of lexicography. Although this bibliography primarily provides German references it also includes references from English and the Nordic and Romance languages.

Besides his own publications Wiegand made a huge contribution as editor and co-editor of a number of scientific journals and book series. He was co-editor of the Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik, Lexicographica: International Annual for Lexicography/Revue Internationale de Lexicographie/Internationales Jahrbuch für Lexicographie, the book series Reihe Germanistische Linguistik, the Wörterbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft and Lexicographica Series Maior. In 1982 he realised the need for a comprehensive series of textbooks covering all subfields of the broad discipline of linguistics. Consequently he co-founded the series Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, and was co-editor and editor of this series of text books that reflect the state-of-the-art of linguistics and communication science. In the 2013 volume Dictionaries, An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography, Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography Wiegand gave a new discussion of a number of dictionary structures introduced in earlier publications. Although he explicitly stated that his discussion focused on structures of printed dictionaries the transfer from printed to online dictionaries has already benefitted substantially from these structures because with minor adaptions many of them can be employed in the planning and compilation of online dictionaries.

Wiegand was one of the participants of the LEX’eter conference (1983) which preceded the founding of EURALEX. His paper at this conference “On the Structure and Contents of a General Theory of Lexicography” was published in the first volume of the series Lexicographica Series Maior. His involvement in establishing this series and his participation in the founding of EURALEX signalled his future role as academic organiser. He initiated a number of scientific colloquia, workshops and conferences, e.g. the International Copenhagen Colloquium, the Heidelberg Lexicographic Colloquium as well as the Colloquium on Lexicography and Dictionary Research, bi-annually hosted in Eastern Europe.

One of Wiegand’s last major endeavours was his participation as leading editor of the Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung/Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. The first volume of this four-volume project was published in 2010 and the second volume in 2017. An important aim of this publication, in which German lexicographic terms are coordinated with equivalents in Afrikaans, Bulgarian, English, French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Russian, is the standardisation of lexicographic terminology. Wiegand dedicated a lot of time, effort and intellectual innovation to this project that kept him involved up to the very last days of his life. During our last telephone conversation, four days before his death, he discussed the future of this project with me and gave some instructions regarding the continuation of the work and what has to be done.

HEW, the initials can also be read as High Energy Wanderer, received well deserved recognition for his work, including honorary doctorates from the Aarhus School of Business, the University of Sofia and Stellenbosch University. The main recognition, however, will be the continued influence of his comprehensive legacy.

With the death of Herbert Ernst Wiegand the metalexicographic discipline has lost a vital, prolific, innovative and academically balanced role player. He will be missed but his memories and his work will live on.

Rufus H Gouws

Stellenbosch University

South Africa

rhg@sun.ac.za